In: Museum of Nonhumanity (Ed. Gustafsson&Haapoja, 2020)

In: Taiteen kanssa maailman äärillä (Toim. Seppä, Anita ja Johansson, Hanna. Parvs, 2021)

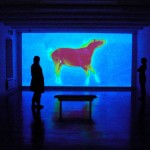

Museum of Nonhumanity is a utopian museum in the form of a 70-minute, 10-channel video installation that displays the division between human and animal, and the resultant oppression. The content of the video installation is made up of archive materials, selected quotations from key works of the tradition of western thought, and dictionary or encyclopaedia definitions that exemplify the mechanics of animalization in the history of western culture.

The Museum interrogates the way we interpret ‘animal’ and ‘human’ as ecological and biological species concepts, and suggests that moves towards inter-species justice overlook the ways in which conceptual discrimination between human and animal in western thought has acted as a tool for marginalizing and oppressing humans and other species. Here I will examine the distinction made between animal and human via three different conceptual frameworks: first, as a species concept that references biological categories; then as a key question for posthumanist thought about the structural connection between the concepts of human and animal; and finally as a demand, arising from decolonial frameworks, to locate the boundary between human and animal within the colonialist paradigm of racialization.

Speciesism and the circle of rights

In human-rights discussions the animal-rights movement is often seen as a pastime of a white elite, which betrays that elite’s lack of concern for human-rights issues. Inside the animal-rights movement, meanwhile, the accentuation of the intrinsic value of humanity looks like a negation of the rights of nature and other species. Underlying this conflict is often the way in which the two sides view the human/animal distinction primarily as a species question. When humanity is seen as a synonym for the species Homo sapiens, and animality, in turn, as a common denominator for all other species, “animals” are seen as a single group who compete with marginalized human groups for recognition of their rights.

The concept of speciesism made famous by the moral philosopher Peter Singer derives from this basic configuration.i The term speciesism identifies the same mechanism as being behind the oppression of animals as is behind racism or sexism: an arbitrary marker (skin colour, gender, species) has been co-opted to justify oppression, even if in reality the issue is simply one of subjugation. The background to Singer’s thinking is Kant’s moral theory, which roots human dignity in the capacity for self-reflection and autonomous thought.ii According to Kant, animals do not have these capacities, and are consequently only means, not ends in themselves. Singer points out that, in reality many animals are capable of self-reflection and are also autonomous, while many humans – for example, those with severe disabilities or illnesses, the very young or old – are not.iii For the argument to be coherent, the inherent value of a living being and its fundamental rights should be formulated according to the individual’s actual attributes, and not species boundaries. This would potentially move some humans into a category with limited human rights, and correspondingly make some animals the holders of a variety of fundamental rights to be determined case by case. To those who are worried that shifting human rights onto a sliding scale makes human individuals vulnerable to exploitation, Singer replies that in current thinking the price of that fear is paid by the billions of animals who have no rights at all.iv

The notion of non-human animals possessing cognitive capacities that forms the basis of Singer’s argument is nowadays a universally acknowledged fact in zoology and other science disciplines. Research data on the abilities of non-human animals to use language, form social relationships, use tools, and even view the world aesthetically – all abilities that were previously seen as exclusively human characteristics – has shattered the idea that human beings differ biologically from all other creatures. Faced with scientific evidence and the sixth extinction the idea of animals having legal rights has broken out of the margins and moved closer to the mainstream.

The Nonhuman Rights Project founded by the US lawyer Steven Wise has long campaigned for the recognition of the fundamental rights of non-human animals, and in recent years NHRP campaigns have reached as high as the state supreme court.v The NHRP’s arguments echo Kant’s moral theory and the Singerian conceptualization of speciesism: According to Wise, it is specifically the capacity for autonomy that is the basis of human rights, and if we take this seriously, many autonomous animals that also have human-like cognitive abilities, such as chimpanzees, orcas and elephants, should be moved from the category of objects to the category of persons possessing legal rights.vi

NHRP’s strategy is to bring court cases on behalf of captive animals with the aid of the habeas corpus method. A writ of habeas corpus demands that the court investigate whether the detention or imprisonment of a person has been done lawfully, and compels the prosecutor either to free the detained person or to charge them with a crime.vii This judicial procedure, which dates back to the middle ages, has been used in historic anti-slavery trials, which have then served as precedents in proving the illegality of slavery. Underlying the NHRP’s argument is the idea of the historical advance of fundamental rights in ever-expanding circles: first, slavery was banned; then came recognition of the rights of women, children, people with disabilities and other minorities; and now it is the animals’ turn. So, the NHRP’s approach, although radical, does not call into question the figure of the autonomous, Kantian human being as the norm for determining legal rights. That is why its potential for bringing non-human beings within the circle of rights is limited: the less human-like a being is, the harder it is to justify its inclusion in the category of persons with rights.

Another problem with the concept of speciesism is the way it overlooks the fact that universal, equal human rights have not been implemented fairly, and that a large portion of the world’s human beings are still excluded from rights. The understanding of the concepts of animal and human as a division rooted in biological species is echoed in discussions of social justice in which human uniqueness is specifically seen as the foundation of human dignity and legal rights.viii From this viewpoint the biggest problem is not the division between human and animal, but the porousness of that divide: a substantial portion of humans are in reality treated “like animals”. When the concept of justice is founded on human exceptionality, any attempt to dismantle the division between human and animal endangers the whole basis for social justice. The way the NHRP compares the plights of enslaved humans and of animals kept in zoos has prompted criticism for precisely that reason: after all, throughout the ages, the oppression of humans has been justified specifically by comparing them to animals.ix

The inability of the mainstream animal-rights movement to answer this challenge deepens the rift between the two fronts. Carol Adams applies the linguistics concept ‘absent referent’ in her examination of the violence hidden underneath language.x For example, “meat” is a referent that conceals beneath it the real animal and its actual suffering. According to Adams, the way animal-rights movements compare the treatment of animals to slavery operates on the same mechanism: the oppression of humans becomes a rhetorical tool used to talk about animal suffering, and thus violence experienced by humans is concealed or even instrumentalized.xi In the process, a mechanism that nullifies violence and makes it invisible, and under which countless humans still live, is reproduced. When the human/animal division is understood as referring to a boundary that divides species, the consequence is almost inevitably a conflict in which human rights and animal rights are opposed to each other, or even mutually exclusive. Posthumanist thinking seeks to bridge that chasm by viewing the concepts of human and animal not as biological categories, but as social constructs.

The unstable construct of humanity

Human and animal are not in reality biological concepts that refer to species. Homo sapiens is one of the great apes and belongs to the continuum of species just as other animals do. Modern zoology has overturned every attempt to define human uniqueness on the basis of biological difference. Science has failed to demonstrate that there exists any property that is unique to the human species, and which is absent from all other species, nor is there any one factor that unites all other species, and which is correspondingly absent from humans. As Matthew Calarco writes, the question of the animal actually contains two different questions: one concerns conceptual opposition between human and animal, the other the concrete relationships between humans and other species.xii But it is impossible to dismantle the violent relationship between humans and other species without first confronting the construction of the binary opposition human/animal in the Western tradition of thought.

The numerous strands of posthumanism are united by their critical approach to Greco-Roman political theory and to the essentialist understanding of the figure of the human being in Enlightenment thinking. Zakiyyah Iman Jackson writes about how these discussions often draw on the writings of poststructuralism and especially of Michel Foucault, which present the human figure as a construct tied to a particular paradigm of knowledge, not as a natural state of affairs. If the distinctive ‘being’ of the human is replaced by the idea that the human is a product of a particular historical and socio-epistemic system, it is also possible to call into question and dismantle the concept of the human.xiii

One main starting point for posthumanist theories is that humans have humanized themselves by rejecting their own animality. Dismantling the human/animal opposition is thus a crucial measure for re-imagining the concept of the human. Giorgio Agamben applies Foucault’s analysis of the relationships between biopolitics and democracy to the construction of the human/animal polarity in a way that is useful for critical animal studies and posthumanism. In The Open – Man and Animal (2004) Agamben traces the distinction between human and animal from the wellsprings of western thought to modern philosophy.xiv Agamben uses numerous examples to demonstrate how the attempt to separate humanity from its animal body constitutes a constantly recurring problem for western thought.xv A common feature of Agamben’s examples is the inability that recurs throughout history to define the human in positive terms – the definition is always done through a negation of the animal. The western conception of the human is founded on this negation process, which perpetually and forever unsuccessfully seeks to separate humanity from the animal. This process is possible because, ever since Antiquity, it has been thought that the human is made up of two different levels: on the one hand, the human being is the basis of organic life or the animal-body, and on the other hand, it is, as it were, the layer of humanity that exists on top of it.

In ancient Greek thought, which also defined Aristotle’s philosophy, zoē describes the basic form of life common to all living things, while bios describes the good, political life characteristic solely of humans. The human is the only being that combines both zoē and bios: bios is, as it were, the layer of social life on top of the basic form of life. It is precisely this dual nature and the juncture or fissure that it produces that makes it possible to strip away the humanity from a human – i.e. returning the person in the eyes of the law to being the animal-body hidden beneath the form of “humanity”, so that the laws that protect a person who possesses legal rights and obligations do not apply. Agamben calls this historical process the “anthropological machine” – a lethal mechanism at the core of western thinking that makes anyone potentially “bare life”.xvi

But Agamben is not interested in the figure of the animal or in the plight of concrete animals. The figure of the animal is linked in his thinking with the mechanisms of violence of western political theory, mechanisms that ultimately make totalitarianism and extermination camps possible.xvii For posthumanist thought Agamben’s theory offers tools for interpreting the concepts of the human and the animal, not as species concepts, but as terms that define a being’s relationship with the law and the rights conferred by law. If there is no natural positive basis for humanity and the only thing that separates the human from the animal is that the human “recognizes itself as human”, then an animal can be literally anyone or anything. Human and animal are, thus, not biological, but social and moral categories. Cora Diamond criticizes Singer’s speciesism by pointing out that in the real world moral categories do not come about by observing differences in the natural world, but by naming. The naming of one being as “human” and another as “animal” discursively produces two mutually different beings that are subject to different moral norms and legal principles.xviii

Dehumanization is thus not such an effective mechanism of violence because some humans are more like animals. It works because “animal” is not a species concept. “Animal” means a being that is killable, which in law means a non-human, and hence also a non-person that cannot have rights. In the conceptual system in which human and animal are each other’s binary opposites, everything that is associated with the human (dignity, rights, status) is absent from the very outset from the definition of animal.xix Violence directed at literal non-human animals thus also produces the category of ‘humanity’ protected from violence. As Maneesha Deckha writes, human-to-human violence that resembles the normalized violence directed at animals makes that violence more acceptable, precisely because violence directed at non-human animals constitutes the foundation of humanity. Violence directed at animals thus also constitutes an example and testing ground for the dehumanization of humans.xx The animal thus emerges as a category whose most important function is to create a space where it is possible to commit violence in broad daylight. Because the category of ‘animal’ exists, anyone can be thrust into that space, where they can then be treated “like an animal”.

The category of animal can thus in practice include anything and anyone, regardless of species. Because the ideal human of the western tradition of thought is the white, European man, anyone who deviates from that norm is in danger of being animalized. Seen from this viewpoint racism, sexism and xenophobia are all forms of animalization: the structure of animalization is itself a necessary precondition for them. Cary Wolfe sees the biopolitical field as a “species grid” or matrix, its nodes being humanized human, humanized animal, animalized human, and animalized animal.xxi Instead of a binary division into human/animal, the biopolitical hierarchy appears in the light of Wolfe’s thinking more like a pyramid, with the protected zone of the rights-bearing subject located at its pinnacle, and the substratum of object-beings made to be killed on its lowest level. The concepts of human and animal act as levers in this structure, ceaselessly moving beings up and down.

Posthumanist thinking thus approaches the concepts of human and animal as social constructs intrinsically bound up with the mechanisms of biopower and violence. Thus, the conceptual opposition of human/animal already produces the structures in which any encounter with other species occurs: already beforehand, animalization governs how we approach other species. Seen through the lens of animalization non-human animals are irrational, bloodthirsty, hypersexual, primitive, simple – in other words “women”, “blacks”, “natives”, “homosexuals”, “the disabled”, i.e. everyone that is categorically rejected by the ideal of humanity as defined by Eurocentric white supremacy and the patriarchy.

No analysis of the encounter with other species can be made without taking into account how the mechanics of animalization also enable the oppression of human groups and individuals. Consequently, it is not an adequate goal of rights struggles to get one or a few species across the human/animal dividing line if that very line is to be left where it is. The ultimate goal should be a fundamental questioning of that division and the construction of a non-anthropocentric ethics.

Racialized animal – animalized human

Several thinkers who approach the concept of the animal from the viewpoint of postcolonial and decolonial thinking criticize both the mainstream animal-rights movement and the posthumanism that derives from the Continental philosophy tradition for not taking into account the relationship between modern racism and the human/animal polarity. According to them, the critique of the western conception of the human and the related mechanism of animalization also has a long history in non-western traditions of thought and in postcolonial theory, which posthumanist thinking rarely takes into account.xxii In these traditions dismantling the concepts of animal and human is not just a theoretical problem, but literally a deadly serious task that affects the necessary preconditions for human life and liberty. From this viewpoint posthumanist thought that disregards non-western and postcolonial traditions of thought and the knowledge they produce is in danger of reviving the ideals of colonialist European thinking.

According to the sociologist Ramón Grosfoguel, the universalization of the western conception of knowledge was preceded by a wave of genocides and epistemicides.xxiii The idea of the objectivity and universality of the western tradition of thought and its methods – still often prevalent in western academic research – is only possible because other traditions of thought have been concretely destroyed. Grosfoguel identifies four genocides/epistemicides that preceded the universalization of the knowledge ideals of the enlightenment: against Muslims and Jews in the conquest of Al-Andalus; against the indigenous peoples of the Americas; the enslavement of large sections of the African population; and the destruction of women’s traditional knowledge in witch hunts. Descartes’ famous phrase “I think, therefore I am” was only possible because it was preceded by centuries of white Europe’s “I conquer, therefore I am”.xxiv Western science is founded on colonialist violence. At the same time, it is also a foundation for the current conception of the human, which is determined by the logic of racializationdo s (de to afctual genoocide which the old way of being human is endangered .

The philosopher Syl Ko writes that the mechanism of racialization produced by European colonialism also fundamentally changed the way the concepts of human and animal are understood.xxv Ko points out that understanding the human/animal divide within the framework of today’s world also requires taking into account the logic of racialization. As Grosfoguel says, the encounter between the Spanish colonialists and the indigenous peoples of the Americas put into question the humanity of what in the eyes of the colonialists were “people without religion”, and who thus also potentially had no soul. If, in the 16th-century European worldview, humanity was primarily defined by the individual’s relationship with God, a human being with no relationship with the divine recognizable to Europeans appeared to be a person who lacked the most essential element of what makes someone human. Eurocentric racism thus emerged as a way for European colonialist conquerors to construct within the concept of the human an ontological hierarchy that divides humans proper from ‘sub-humanity’.xxvi The transatlantic slave trade universalized this principle and inscribed blackness as a signifier for ‘sub-humanity’, while white Europeanness signified pure humanity.

As Ko says, the construction of humanity in such a thought model is fundamentally different from what is proposed by a universalist, posthumanist critique. The conceptual opposite presumed by the human proper is no longer so much the non-human animal as the racialized ‘sub-human’.xxvii Other species and their historical oppression get drawn into this configuration and accordingly racialized, the grounds for this being their assumed proximity to the ‘sub-human’ in the great chain of being. The animal and the racialized human are thus not distinct positions in the identity game, positions that compete with each other for recognition, but two different manifestations of the Other required to maintain the Eurocentric, colonialist image of humanity. This also has consequences for the human-rights viewpoint: According to Deckha, humanism’s idea of universal, equal human rights never really secures minorities’ rights, because the humanist conception of the human is founded on the exclusion of racialized and animalized others.xxviii Destabilizing the conceptual boundary between human and animal would be a better approach. On the other hand, talking about animal rights as an expansion of the circle of human rights does not take into account the interweaving of racialization and animalization. As Che Gossett writes: “For many in animal liberation and animal studies, abolition is imagined as teleological; first slavery was abolished and now forms of animal captivity must be, too. It is as though animal is the new black even though blackness has already been racialized through animalization.”xxix Thus, the concepts of human or animal cannot be dismantled without also dismantling the mechanisms of racism – and correspondingly, as Syl Ko emphasizes, dismantling racism requires a re-conceptualization of the relationship between human and animal.

For Agamben the concentration camp is an extreme manifestation of modern biopower without a historical parallel.xxxAlexander Weheliye, nevertheless, asks what Agamben’s analysis would look like if he had taken the transatlantic slave trade and not the holocaust as his starting point.xxxi From this viewpoint, within the realm of the sovereign we can see a third possible position: that of an object that can be owned. Being able to be owned links both non-human animals and racialized, enslaved humans to the sovereign field. In the biopolitical arena the object (of rights) is thus neither an outlawed human being nor a sovereign power, but the thing that makes them possible and which is their foundation (land, animals, anonymous nature as a resource, enslaved humans, wombs controlled by the patriarchy, and so on). Although Agamben criticizes the ‘anthropological machine’ that violently produces the division between human and animal in western thought, he still inhabits an anthropocentric, Eurocentric framework, seen from which the racialization of the concept of the animal is invisible. Zakiyyah Iman Jackson also criticizes posthumanism’s blindness to non-western traditions of thought and their critique of the enlightenment’s conception of the human. Other ways of conceptualizing the human have always existed, and still do. Jackson asks whether it might be the case that the ‘beyond humanity’ proposed by posthumanism points not to a temporal, but to a geographical beyond – an area beyond the west.xxxii

Bringing racialization into the “animal question” opens up a channel to the constructive articulation of the relationships between human rights and other species. This viewpoint also makes possible an alliance between antiracist action and the animal-rights movement in a way that is difficult, if the posthumanist critique does not take into account the link between racism and the modern world’s animalizing mechanisms, or non-western critiques of the enlightenment conception of the human; and even impossible, if the human/animal polarity is understood as following a species boundary. In their bookAphro-Ism – Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters (2017) Syl Ko and Aph Ko set out an antiracist vegan practice, Black Veganism.xxxiii The sisters stress that Black Veganism is not only a veganism practised by non-white people, but also an ethical theory. Refusing to take part in the oppression of non-human animals is also a resistance to white supremacy and the logic of animalization inscribed in it.

Thus, anyone can practise Black Veganism, but racialized humans have special experiential knowledge of what it is like to be shut outside of humanity. That experience can lead to an understanding that ‘animal’ is a polymorphous social construct that includes both humans and other species.xxxiv Hence, the viewpoint of Black Veganism offers a place from which the human rights movement can approach other species via an antiracist, inter-species alliance. As Ko points out, by the same token the animalization of other species is inscribed into their embodied experience. But even if the animals assigned as other species experience oppression, they do not internalize their own animalization like humans do. The oppression of humans and other species are thus not psychologically identical: other species can hardly have the ontological experience of a lack of humanity resulting from internalized racism of the kind Syl Ko describes. In Ko’s words, they have epistemic resilience to the logic of animalization,xxxv which makes them good allies for critics of Eurocentric humanism.

In Conclusion

The transatlantic slave trade is the foundation of modern capitalism. For example, the British cotton factories and working class could not have come about without cotton plantations run on slave labour. Thus, the mechanisms of animalization cannot be understood without their links to the history of European racism, colonialist violence and capitalism. Capitalism needs animal bodies: it is dependent on the non-human beyond the reach of rights and made killable, whose labour, body and reproduction are a central precondition for capitalist production. This class is not defined according to species boundaries, but is in constant motion: the pinnacle of the biopolitical pyramid takes the form of a white space of humanity and legal rights, to which, for example, charismatic megafauna – lions, tigers, orcas, chimpanzees, elephants – can be raised, while the base of the pyramid is constituted by an ever-greater number of humans and individuals of other species who have been instrumentalized as disposable parts of the production economy. A critique of capitalism thus has to begin by challenging not only the concept of class, race and gender, but also that of the animal.

If posthumanist art or critical animal studies view the animal question solely as a problem related to the question of species, it wastes an opportunity to create a connection with movements promoting social justice. The worrisome whiteness of posthumanist and animal-rights discourses does not solely tell us that these academic and art spaces are closed structures of privilege. Rather, it says that their way of articulating the question of what comes after humanity does not appear meaningful to those humans who find themselves concrete objects of the violence associated with the concepts of animal and human. It is also problematic to produce information about a phenomenon if an essential aspect of it – in this case, the connection between the concept of the animal and structural racism – is seen as a side issue in the discourse. Thus, at the worst, the knowledge produced, instead of calling into question an epistemology based on colonialist violence, actually carries on the epistemicide referred to by Grosfoguel.

Intersectionality and decolonization are terms that are also in danger of being diluted if they are adopted as part of the Eurocentric academic tradition, without challenging the underlying values of this canon and the institutions and practices that support it. It is crucial to understand that decolonization is not a metaphor, as Eve Tuck powerfully argues.xxxvi Along with many other things, decolonization means restoring the land rights of indigenous peoples and recognizing their right to national self-determination and self-governance. Every act of knowledge production that aims at the decolonization – i.e. at side-lining the white, Western perspective – should also commit to supporting this concrete goal.

The ‘after humanity’ called for by posthumanism will not come about if we do not let go of the concept of the human elevated to the status of universal. That universality is a smokescreen that conceals the ascendancy of whiteness and Eurocentricism. The “human” of the modern, western tradition of thought is always defined by racialization . This challenge also presents itself in the opposite direction: in social-justice movements it is often difficult, if not impossible, to elevate the rights of nature and other species alongside human-rights struggles, because in the short term humanity appears as a refuge from the violence of animalization. That is why in the critique of humanism put forward by posthumanism there needs to be an emphasis on an analysis in which the racist, colonialist roots of humanism are made visible. Only then will we be ready to break out of the paradigm of the human into a time beyond animality.

Museum of Nonhumanity makes visible the way that the concepts of sub-human and animal are rhetorical devices that justify violence. The Museum reveals the conception of the human at the core of the western tradition of thought to be the basis for the oppression directed at both human and non-human beings. Dehumanization generally occurs first on the level of language and conceptualization, and then in action. The ten different themes of the Museum of Nonhumanity exhibition examine this act of definition as it occurs on the level of language in different sub-areas of western culture. The final theme of the exhibition is “the museum”, which as a historical institution is an intrinsic part of the mechanics of dehumanization. The institutions that produce and display knowledge justify hierarchies that have material consequences, often deadly ones. A museum can speak something into truth, in which case it becomes a part of social reality. Thus Museum of Nonhumanity is, in Laura Gustafsson’s words, “a performance in which the actor’s role is played by the public, which by believing in the Museum’s narrative of the end of dehumanization makes it momentarily true.” At the same time, the term museum expands also to refer to institutions that are responsible for showing art more broadly. If posthumanism aims at a world in which the normative “human” produced by white supremacy and patriarchy as an image of themselves has been side-lined, what will that world’s museum or its viewers be like? Can a museum – an institution whose history is specifically rooted in the construction of that normative image of the human and in the maintenance of othering representations – truly be decolonized, or do we need to seek to move towards traditions in which not only the conception of the human, but also the conception of art and creativity, are situated differently?

In Museum of Nonhumanity these and other open questions are considered in various venues in the form of discussions, lectures and workshops tailored to match the local situation. Through these discussions Museum of Nonhumanity also calls into question the premises for its own existence. It does not seek to be a solution, nor to paint an image of a new paradigm. Utopian thinking becomes dangerous if it projects onto the future an idealized, totalized version of the current value system. Museum of Nonhumanity is a bridge towards something that we cannot even imagine; a bridge that has been built to break through to the other side that follows the transition.

References

Adams, Carol 2015. The Sexual Politics of Meat. New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Agamben, Giorgio 2004. The Open – Man and Animal. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Agamben, Giorgio 2000. Means Without End. Notes on Politics. Minneapolis / London: University of Minnesota Press.

Agamben, Giorgio 1998. Homo Sacer – Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Boisseron, Bénédicte 2018. Afro-Dog – Blackness and the Animal Question. New York: Columbia University Press.

Calarco, Matthew and DeCaroli, Steven 2007. Giorgio Agamben – Sovereignty & Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Calarco, Matthew 2008. Zoographies – The Question of the Animal from Heidegger to Derrida. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deckha, Maneesha 2010. “The Subhuman as a Cultural Agent of Violence.” In: Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume VIII, Issue 3, 2010 pp. 28-51

Diamond, Cora 1978. Eating Meat, Eating People. Philosophy, Vol. 53, No. 206 (Oct. 1978), pp. 465-479. Cambridge University Press on behalf of Royal Institute of Philosophy.

Filar, Ray 2016. Cruising in the End Times: An Interview with Che Gossett. In Verso Blog: https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3016-cruising-in-the-end-times-an-interview-with-che-gossett (16.11.2019)

Gossett, Che 2015. Blackness, Animality and the Unsovereign. In Verso Blog: https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2228-che-gossett-blackness-animality-and-the-unsovereign (16.11.2019)

Grosfoguel, Ramon 2013. The Structure of Knowledge in Westernized Universities

Epistemic Racism / Sexism and the Four Genocides / Epistemicides of the Long 16th Century. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, XI, Issue 1, fall 2013, pp. 73-90.

Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman 2013. Animal: New Directions in the Theorization of Race and Posthumanism. Feminist Studies 39, No. 3, pp. 669-685.

Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman 2015. Outer Worlds: The Persistence of Race in Movement “Beyond the Human”. In GLO: AJournal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, special issue on Queer Inhumanisms, eds. Mel Y. Chen and Dana Luciano. Volume 21, Numbers 2-3, June 2015. Published by Duke University Press.

Jackson: Zakiyyah Iman 2016. Losing Manhood: Animality and Plasticity in the (Neo)Slave Narrative. In Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences. Volume 25, Numbers 1 & 2, Fall/Winter 2016, pp. 95-136. Published by Duke University Press.

Johnsson, Walter 2017. To Remake the World: Slavery, Racial Capitalism, and Justice.

In Boston Review. A Political and Literary Forum. (Forum 1: Race Capitalism Justice). Printed from https://literature-proquest-com.ezproxy.princeton.edu

Kant, Immanuel 1997/1775-80. Lectures on Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, Claire Jean 2015. Dangerous Crossings – Race, Species and Nature in a Multicultural Age. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ko, Aph and Syl 2017: Aphro-Ism – Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters. New York: Lantern Books.

Kurki, Visa 2017a. Animals, Slaves, and Corporations: Analyzing Legal Thinghood. German Law Journal. Vol. 18, No. 05.

Kurki, Visa 2017b. Why Things Can Hold Rights: Reconceptualizing the Legal Person. In Legal personhood: Animals, Artificial Intelligence and the Unborn. Eds. Kurki, Visa A.J. and Pietrzykowski, Tomasz. The Law and Philosophy Library, Vol. 119. Springer International Publishing.

Ly, Palang 2019. An Interview with Syl Ko – Activism in terms of an epistemological revolution. In Tierautonomie. February 2019. https://simorgh.de/about/an-interview-with-syl-ko/

Nylén, Antti 2014. Sika on worldn neekeri. Suomen Luonto 9/2014.

Ryder, Richard D. 2010. Speciesism Again: the original leaflet. Critical Society, Issue 2, Spring 2010. http://www.veganzetta.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Speciesism-Again-the-original-leaflet-Richard-Ryder.pdf (27.5.2019)

Singer, Peter 2009a. Speciesm and Moral Status. Metaphilosophy, Vol. 40, Issue 3–4, July 2009, pp. 567-581. Metaphilosophy LLC and Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-9973.2009.01608.x

Singer, Peter 2009b/1975. Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, Reissue edition (February 24, 2009).

Tanner, Julia K. 2009. The Argument from Marginal Cases and the Slippery Slope Objection. The White Horse Press. Environmental Values 18 (2009), pp. 51–66.

Tuck, Eve ja Yang, Wayne K 2012. Decolonization is not a Metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1-40.

Weheliye, Alexander G. 2014. Habeas Viscus – Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Wolfe, Cary 2013. Before the Law: Humans and Other Animals in a Biopolitical Framework. London and Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wolfe, Cary 2003. Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory. London and Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Press and online sources:

Hubara, Koko 2016. Sikamaista vertailua. Ruskeat Tytöt blog, Lily.fi. 26.5.2016.

https://www.lily.fi/blogit/ruskeat-tytot/sikamaista-vertailua/ (11.11.2019)

Julia Marsh 2019. Lab chimps likened to enslaved blacks at animal-rights trial. New York Post 27.5.2015.https://nypost.com/2015/05/27/lab-chimps-likened-to-enslaved-blacks-at-animal-rights-trial/ (11.11.2019)

The Nonhuman Rights Project

https://www.nonhumanrights.org (23.5.2019)

https://www.nonhumanrights.org/litigation/ (23.5.2019)

Museum of Nonhumanity – Epäihmisyyden museo

http://museumofnonhumanity.org (23.5.2019)

i The concept of “speciesism” was developed by the philosopher Richard Ryder in 1970 (see Ryder, 2010). It was subsequently brought to the awareness of the general public in Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation – A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals (1975).

ii Kant 1997. “Animals are not self-conscious and are there merely as a means to an end. That end is man.” Kant 1963, 239.

iii Singer 1990, 568-570.

iv Singer 1990, 578-581.

v The Nonhuman Rights Project, https://www.nonhumanrights.org

vi The Nonhuman Rights Project website puts it like this: “The Nonhuman Rights Project is leading the fight to secure actual legal rights for nonhuman animals through a state-by-state, country-by-country, long-term litigation campaign. Our groundbreaking habeas corpus lawsuits demand recognition of the legal personhood and fundamental right to bodily liberty of individual great apes, elephants, dolphins, and whales held in captivity across the US. With the support of world-renowned scientists, we argue that common law courts must free these self-aware, autonomous beings to appropriate sanctuaries not out of concern for their welfare, but respect for their rights.” https://www.nonhumanrights.org/litigation/ (11.11.2019)

vii See Nonhuman Rights Project website: “Habeas corpus is a centuries-old means of testing the lawfulness of one’s imprisonment before a court. It was used extensively in the 18th and 19th centuries to fight human slavery, and abolitionists often petitioned for common law writs of habeas corpus on behalf of enslaved individuals. The most well known such case is Somerset v. Steuart (1772) in which the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales granted the writ to a human slave, freeing him unequivocally and essentially transforming him from a legal thing to a legal person. We argue common law courts should do the same for our nonhuman clients.” https://www.nonhumanrights.org/litigation/ (11.11.2019)

viii The “argument for marginal cases” is a term used in animal rights theory and linked to a problem that arises out of the partial overlap between the cognitive abilities of humans and other species. The argument seeks to show that any categorical moral separation of human and animal is impossible, because some animals have abilities that not all humans have. For example, a new-born human does not have a capacity for language or autonomy, while many nonhuman animals are able to express themselves in language as soon as they are born. According to the counterargument moral categories are based on generalizations behind which are the average differences between species: because humans in general are independent, they should be treated as a coherent moral category. (see, e.g. Tanner, 2009.)

ix For example, New York Post headlined an action taken by the Nonhuman Rights Project in New York state’s supreme court as follows: “Lab chimps likened to enslaved blacks at animal-rights trial” NY Post, 2015, https://nypost.com/2015/05/27/lab-chimps-likened-to-enslaved-blacks-at-animal-rights-trial (11.11.2019)

x Adams says on the Earthling Liberation Kollective website: “The absent referent is a term I politicized in “The Sexual Politics of Meat”. The absent referent is the literal being who disappears in the eating of dead bodies. There are three ways I see the absent referent functioning. Literally, an animal killed to become food or “meat”. Physically, the animal is dismembered – cut up, generally – sold off as body parts. So the reminder that the animal was a full being, living a life, disappears. Then the third way is metaphorically. Their oppression, someone else’s oppression, becomes a metaphor for another group’s oppression. Where being treated “like a piece of meat” is, would be an example of the metaphor of the absent referent.” https://humanrightsareanimalrights.com/2016/01/01/carol-j-adams-politics-and-the-absent-referent-in-2014/ (11.11.2019)

xi In 2015, the essayist Antti Nylén wrote a column in Suomen Luonto (Nature of Finland) magazine with the heading “Sika on maailman N-” (the pig is the N- of the world). The text appropriated Yoko Ono’s famous saying: “Woman is the N- of the world”. The text, to my mind justifiably, enraged many minorities, and is a model example of the absent referent: In Nylén’s case a globally oppressed human group was made a means for speaking about the subjugation of another being. (Nylen 2015. See also Hubara 2016).

xii Calarco 2008, 2.

xiii Jackson 2013, 670.

xiv Agamben 2004.

xv Agamben 2004. For Agamben the Ancient Greek terms describing “life” zoē and bios form the foundation for Aristotle’s thinking, in which life is for the first time arranged hierarchically; the organic lifeforce that unites all of life and the sensoriness that links all animals culminate in human rationality. Starting with Aristotle’s thinking, these levels are discernible in the human figure: the level of general life, the level of the animal, and the highest level of the human being. This structure is echoed at the roots/origins of modern science in the thinking of the enlightenment thinker and anatomist Marie François Xavier Bichat, in which the being of organisms is seen through a kind of double exposure: present in an animal, on the one hand, is its “organic life” and, on the other hand, its sensory or perceptual life. For Christian eschatology the Resurrection is a headache, since even if specifically the human soul comes from God, it inhabits an animal body. What, then, happens to the animal body in Heaven? From the viewpoint of modern science and taxonomy the attempt to define an essential difference between humans and other great apes is an impossible task, which the father of modern taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus, tries to get out of by saying that the human is an ape that “recognizes itself as human”. In Heidegger’s thinking, in turn, between Dasein and the animal there is an “unbridgeable chasm”. Agamben also deals with the problem of the end of history in 20th century critical theory in the light of the human/animal distinction.

xvi As Agamben says: “Both [the premodern and the modern anthropological] machines are able to function only by establishing a zone of indifference at their centers, within which – like a ‘missing link’ which is always lacking because it is already virtually present – the articulation between human and animal, man and non-man, speaking being and living being, must take place. Like every space of exception, this zone is, in truth, perfectly empty, and the truly human being who should occur there is only the place of a ceaselessly updated decision in which the caesurae and their rearticulation are always dislocated and displaced anew. What would thus be obtained, however, is neither and animal life nor a human life, but only a life that is separated and excluded from itself – only a bare life.” (Agamben 2004, 37-38.)

xvii Agamben 1998, passim.

xviii Diamond 1978, 470.

xix Ko 2017, 111

xx Deckha 2010, 37.

xxi Wolfe 2003, 101.

xxii See, e.g. Ko 2017; Gossett 2015; Jackson 2013, 2015 and 2016.

xxiii Grosfoguel, 2013.

xxiv Grosfoguel 2013, 77.

xxv Ko 2017.

xxvi Grosfoguel, 2013, 81. See also Ko 2013 and Palang 2019.

xxvii Palang 2013, 10-11.

xxviii Deckha 2010, 45-46.

xxix Gossett describes this idea, for instance, like this: “In contrast to the vision of abolition offered by Douglass, for many in animal liberation and animal studies, abolition is imagined as teleological; first slavery was abolished and now forms of animal captivity must be, too. It is as though animal is the new black even though blackness has already been racialized through animalization. Critiques of “human exceptionalism” and anthropocentrism in critical animal studies often presume that the human in the human/animal divide is a universally inhabited and privileged category, rather than a contested and fractured one. Blackness and its relation to animality and abolition is often left in what Saidiya Hartman and Frank Wilderson call “the position of the unthought.” (Gossett 2015)

xxx Agamben 2000, 37-49.

xxxi Weheliye 2014, 33-36.

xxxii Jackson 2013, 681.

xxxiii Ko 2017, 50-56, 120-127.

xxxiv Ko 2017, 124.

xxxv Palang 2019, 20

xxxvi Tuck, 2012.