Terike Haapoja

Museum of Nonhumanity

Published in: Radical History Review

During the Finnish civil war in 1918 the renowned author Ilmari Kianto called for the extermination of the “wolf bitches” that he saw as a threat to the independence and future of the country. Fought between the working class—who, encouraged by the Russian Revolution, rose up against the owning class—and the nationalist bourgeoisie, the civil war was a class struggle in the wake of the country’s independence. The victory of the new, conservative government was followed by violent suppression of the revolutionaries. The so-called Red Guard fighters were killed en masse, while an estimated 2,500 women and girls as young as fourteen, who had taken up arms alongside their men, perished or were executed in prison camps.i

It is to these women that Kianto refers when he writes:

Wouldn’t it be a proper strategy to take a certain percentage of the enemy’s other sex too—thus giving a moral lesson to the female accomplices of these miserable creatures? In wolf hunting it is the she-wolf rather than the male that makes a better target. For the hunter knows that the bitch will produce new whelps to bring eternal trouble. It has been proven that the Red Guards in the Finnish civil war are beasts, and many of their women wolf bitches; I venture to say even she-tigers. Isn’t it completely insane not to shoot down the beasts that harass us?ii

Kianto’s call for culling of the peasant rebels coincided with a warlike culling of wolf populations. Canis lupus, a previously common animal in the region, was hunted to extinction in the country by 1920, and aggressive wolf hunts aimed at keeping its population at zero continued until the 1970s. In spite of the absence of the animal itself, the wolf has remained a powerful creature in Finnish political mythology, where it functions as a boundary figure between the center and the periphery, the domesticated and the wild, the desired and the unwanted, the dominant and the dominated. While present-day environmentalists seek to protect the population from extinction, for many, wolves symbolize a threat to a traditional hierarchy that runs from God to men, to women, and eventually to nature. For them, maintaining this hierarchy requires constant suppression, justified by vilifying the othered as murderous if liberated. Nearly one hundred years after Kianto, in 2015 an online debater commented on the protection of wolf populations: “I can assure you that HUNTING WILL NEVER STOP. . . . We do know how you protectors have aimed at preventing the hunting, haha in your dreams. I hope we’ll soon get rid of those wolf mongrels.”

…..

Long before being officially acknowledged as a geological era, the term Anthropocene and its periodization has been intensively critiqued. Not only does the proposed geological marker obscure the colonial violence and extraction that underlies it, but it also blames a species for destruction brought on the whole planet by a small minority of its members, thereby repeating the structure of blaming the victim for the violence inflicted on them. While the term has been countered by multiple other, more suitable -cenes (“capitalocene,” “white supremacy scene,” “plantationocene”iii), less attention has been given to examining the word anthropos and the mechanisms by which the culprits of this -cene have been able to act on behalf of and as representatives of the whole of humanity. In fact, one of the most foundational drivers of this planetary-scale violence is the way in which humanity itself has been mobilized as an exclusive category in the Western imaginary.

Humans are, of course, animals. There’s nothing that all other species share that differentiates them from us, nor is there any capacity that humans possess that isn’t possessed also by some other species. As many animal rights theorists have pointed out in the past, the moral and legal permission to exploit and kill other animals with impunity cannot be founded on any essential biological or cultural difference between us and them. Yet the history of Western thought can be seen as an ongoing attempt to ground this division on some quality that humans have, that non- human animals lack. Possessing a soul, rationality, language, tool-making skills or social intelligence are just some of the qualities proposed to carry that function. Giorgio Agamben has coined the term anthropological machine to describe this ongoing operation at the heart of Western thought that tries to ceaselessly, and for- ever unsuccessfully, separate humanity from its underlying animal body.iv

While many instances in the historical development of rights have been bound to political belonging, such as citizenship, the notion of universal human rights anchored these rights to species belonging. Will Kymlicka notes how some of the early theorists of universal human rights made this claim explicitly: humans should have rights exactly and only because humans are not animals.v Here, rights are based on speciesism, which is ultimately just decisionism: some don’t have rights just because the ones in power will so. As Kymlicka points out, this is an absurd reversal of the purpose of the human rights project, which should protect exactly against such decisionism.vi Because the moral divide is ultimately arbitrary, it needs to be constantly reinforced through practices of different treatment. Stem cell research offers a revealing example: while research on human embryos needs to be terminated by the fourteenth day from fertilization, which is considered the point in which individuation begins, research on nonhuman embryos has no such limit, even if as a biological matter they are identical. vii Merely the potential to become human protects some cells from being experimented on, while the lack of this potential dooms others to experiments throughout their development and likely through the lives of the fully grown organisms.

Because humanity emerges in this arrangement as a site of political belonging and privilege, it remains a site of contest. In the history of the Western imaginary, who counts as human has been defined not only in relationship to nonhuman animals but also to human others. Projecting onto cultural others a lack of presum- ably “human” qualities such as language, soul, or rationality has been used to construct the figure of a subhuman that becomes constitutive of the figure of the human proper. Maneesha Deckha writes that postcolonial scholarship has shown that “the rational and autonomous liberal actor always requires an Other through which to establish himself.”viii Thus the history of Western science is built on experimentation on the bodies of enslaved, female, poor, or disabled people, who have not been considered human enough to deserve protection. In the modern era the invention of race has become a primary means of managing the boundary of humanity. Ilmari Kianto’s call for the extermination of Red Guard women as population control was based on the race science of his time, eugenics, that foregrounded the white, able- bodied European man as normatively human.

….

Claire Colebrook chronicles how the figure of the anthropos has always been defined by existential threats in the Western imagination: “he is set apart from all life in the world by his existential fragility.”ixAccording to Colebrook, “To be properly human is to be at risk, to be threatened with falling back into being mere life, a part of the world, becoming nothing but a body without a sense of the globe, man or Anthropos.”x In this narrative, the human is, ontologically, a figure defined by its perpetual victory in a perpetual war against hostile forces that threaten to annihilate it. Our current climate chaos–focused horizon has again been captured by this possibility of the nonbeing of humanity, reinforcing this narrative. Colebrook asks how “one negotiate[s] the genuine brutality of the present without buying into a fantasy of apocalypse that fetishizes humanity by way of a violent destruction of all that renders humanity fragile” and through that justifies disaster capitalism and global states of emergency.xi

Following Colebrook, the “Anthropos” of the Western imaginary needs the other/othered not only as a binary opposite, but also, and maybe more importantly, as a perpetual threat to its existence. While the idea of universal human rights seeks to ensure all people are protected, it’s an obvious fact that all laws, including laws that regulate killing, are always situation specific. Important exceptions to the prohibition of killing include self-defense, war, and states of exception.xiiAnd so, when humanity is defined through an existential threat, these exceptions are always ready to be activated by perceived threats by the other/othered to the human subject. To be threatened is thus not only an experiential condition of “the human,” but a structural condition for the possibility of its existence. Without this threat, the figure collapses. Thus perpetual production of situations where the other/othered is placed in the role of a perpetrator is necessary in order to prove this danger, and through that, to reinforce the identity of “the human.” A mob of white protesters storming the US Capitol is not perceived as an existential threat by a white supremacist legal order, in an atrocious contrast to peaceful Black protestors who are subjected to violent repression. Instead, the mere existence of the peaceful Black protestors legitimates the violence of the white mob. The phrase “the purpose of the system is what it does” is useful here: if the system produces killing of racialized minorities with impunity, that is the purpose of the system.xiii

As Deckha notes, extending rights isn’t enough if the underlying humanism is left intact.xiv In other words, as long as the subject of rights is defined through a negation of an other, those included need to assimilate to this logic and find a new other to constitute their identity as rights holders. Thus the need to reinforce racial and speciesist boundaries is sometimes strongest among those whose belonging is most precarious. Humanity in the Western imaginary appears as an ungrounded category, that is less bound to phenotype than to the logic of decisionism of the powerful and negation of the other/othered, who or whatever they are. As Syl Ko observes, while racialized people are othered through animalization, racial imagination in turn informs how nonhuman animals are perceived.xv In a classical act of gaslighting, power projects on its subjects its own brutality, irrationality, and sexual instinct. In the white supremacist, patriarchal imagination, the categories of subhuman, less human, and nonhuman merge into different variations of nonwhite, non-rational, non-Man.

…..

More recent theories of human rights have diverted from speciesism and instead sought to ground rights on qualities such as vulnerability or precariousness, centering care ethics or capability-based theories.xvi These approaches open a door to continuity with other beings who share these qualities and challenge the species- ism of mainstream understandings of (human) rights. Legal developments are, indeed, moving in this direction, with expansions for the recognition of, for example, children, disabled people, Indigenous peoples, and most recently, some nonhuman beings and entities. Here, humans can be viewed as animals among other animals, whose rights emerge from their (our) embodied animal being instead of some abstract humanity placed on top of it. Yet, while the sphere of rights keeps expanding, forms of violence keep finding ways of existing under new names, too. While “statutes outlawing cruelty coexist with the slaughterhouse,” as Deckha reminds us, de facto slavery also coexists with universal human rights.xvii Expanding the rights framework is an important instrument for bringing groups and entities under ethical consideration and holding up the ideal of basic rights, as well as for challenging existing privileges. Yet, instead of looking for rights as the perfect solution, it is also important to investigate the material relations that enable zoopolitical, dehu- manizing violence toward all species.

If we can view humans as existing on a continuum with other animals in terms of their need for protection, we can also view humans and nonhuman animals as existing on a continuum in terms of oppression. In this view, the categories human and animal appear not as natural groupings but as operations within biopolitical cap- italism that perpetually generate labor force and material to extract from. While it is widely acknowledged that capitalism is in its essence racial, in other words that it relies on racialized populations that are exploited in the periphery of wage labor, it needs to be acknowledged that capitalism is also animal capitalism. The tautology goes as follows: animals are those who can be extracted from; those who can be extracted from are animals. The use value of a body for capitalist production is not species dependent: capitalism needs all kinds of bodies for all kinds of labor. And throughout the history of capitalism, nonhuman animals and people excluded from humanity have been laboring side by side, pulling, pushing, carrying, in different rela- tionships to freedom and bondage, building the world we all now inhabit. Alongside wage labor, itself a form of unfreedom, there has always existed the shadow labor of women and other birthing beings, who reproduce life in the form of new laborers and because of that never quite fully own their own bodies. The necro- and biopolitics of animal capitalism not only make live but force billions of animals into agonizing existence, while millions of people and nonhuman animals are let die as a result of pollu- tion or loss of livable land, or because they are deemed worthless to production.

Today, there’s not a single place on earth not impacted by exploited animal labor, nor a field of production that would not be entangled with what Nicole Shukin calls capitalism’s carnal traffic in animal substances; and there is not a place on earth that is not impacted by the animalization that the white supremacist ideal of humanity relies on.xviii If the position of animals in the face of law is not founded on any essential characteristics in them, the position of racialized people as the other of the white supremacist figure of the human is obviously not founded on any essential characteristics either. The infamous example of the three-fifths compromise is a case in point. While it was beneficial for the slaveholding states to count the enslaved as people when it came to the number of state representatives in federal elections, for the purposes of taxation, the less populous the state, the better. The resulting compromise (counting the slave population as “three fifths of all other persons”) demonstrates how the laws of economics, rather than the laws of nature, decide on inclusion and exclusion, and how belonging to humanity is a question of belonging to the political community rather than of belonging to a species.

When Frederick Douglass writes how the violence imposed on him resembles the violence he in turn is expected to impose on the oxen, what he is describing is not a similarity between him and the animal but the relation to power they share.xix It is not that nonhumans can be caged: it is the cage that constructs the non-human, as well as the human outside the cage. And so, following Maneesha Deckha, to try to protect people from dehumanization by resorting to human rights does not make sense if the category of human has been constructed by excluding from it racialized others. Instead of trying to establish justice on a negation of yet new others, what emerges is a possibility for recognizing animality as a structural position that calls for not only multiracial but multispecies class struggle.

…..

Throughout Western history, museums have been central for managing and reinforcing the white supremacist, patriarchal human-animal boundary. Just the fact that there exist separate museums for “natural” and “cultural” histories establishes these institutions as sites of contest. The campaign to remove representations of Indigenous people from the American Museum of Natural History in New York is one example of this struggle against dehumanization. In a simultaneous move, natural history museums today increasingly describe nonhuman animals as having cultures, moving away from reductive representations. The question remains, however, whether an institution that has been birthed by a colonial, white supremacist culture as a device for this boundary making can be decolonized, in other words cleansed of this exact practice. For a museum always speaks to select groups as its audience, and through this calls them into being as subjects for whom, and from whose perspective, the story of “us” is told. Memorial museums, in turn, can include those already lost by recognizing their passing as grievable, and through this recognition situate them as reminders of a line never to be crossed again. What if, instead of pitting human and nonhuman histories of animalization against each other, the boundary-making practice itself was placed in a museum, with a declaration “never again”?

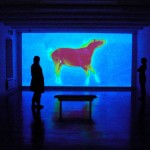

Museum of Nonhumanity, a touring project by Gustafsson&Haapoja, is a utopian memorial museum for commemorating all the victims of the human-animal boundary and the logic of exclusion it sustains. The project’s exhibit, a ten-channel video installation that runs through seventy minutes, consists solely of archival images, encyclopedia entries, and dictionary entries that function as evidence of this conceptual boundary making that precedes physical violence. Focusing on different optics, political scenarios, and motivations, the Museum explores how definitions of animality and nonhumanity function as justification for violence and exploitation of beings of all species in Western history. Instead of being an archive of violent instances, the Museum is an archive of mechanisms and strategies, reasonings, and ideologies that mobilize these categories. Through overlapping stories and rhetorical examples, the exhibit presents animality as a central device for all oppression, a device that is characterized by the fact that it’s not bound to any characteristics but can be bent any way power wants at any given moment. From this bending the self-declared Anthropos, the protagonist of the Anthropocene, builds its unfounded power.

Museum of Nonhumanity is real in the same way all museums are real: its truth value depends on whether people collectively believe in it. Simultaneously, by appropriating the form of a museum, it hails the visitor into being as a subject for whom the Museum is real. Thus the Museum temporarily transforms the world—the whole world!—into one where the human-animal boundary has been placed into a museum and locked into the past. It doesn’t present an alternative to the Anthropos, but destabilizes it so that new modalities of being human can be articulated—while also posing the question of who is the “we” that the Museum, or any museum, speaks for. In each of its iterations, programming by local artists, thinkers, and activists invites others to join in this work.

Gustafsson&Haapoja

The exhibitions, stage work and publications of Gustafsson&Haapoja focus on issues that arise from the anthropocentric worldview of Western traditions. Their first large scale exhibition, Museum of the History of Cattle (2013), presents world his- tory from a bovine perspective; the accompanying book History According to Cattle was published in 2015. The participatory courtroom performance The Trial (2014) explored the notion of nonhuman legal personhood and rights of nature. Museum of Nonhumanity, a touring museum that presents a history of the human-animal binary and how it has been used to oppress beings of all kinds, opened in Helsinki in 2016 and has since toured in Italy, Taiwan, Norway, Denmark, and the UK. The sound installation Waiting Room (2019) and their most recent work Pigs (2021) explore the biopolitics of industrial animal agriculture. Becoming (2020) is a three-channel, three-hour video installation that presents emergent notions of being human that have been shadowed in the Western worldview.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel Heller- Roazen. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998.

Agamben, Giorgio. The Open: Man and Animal. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004. Benjamin, David, and David Komlos. “The Purpose of a System Is What It Does, Not What It

Claims to Do.” Forbes, September 13, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/benjaminkomlos /2021/09/13/the-purpose-of-a-system-is-what-it-does-not-what-it-claims-to-do/ ?sh=52dce3e3887a.

Butler, Judith. The Force of Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind. New York: Verso, 2020. Colebrook, Claire. “The Future Is Already Deterritorialized.” In Deterritorializing the Future:

Heritage in, of, and after the Anthropocene, edited by Rodney Harrison and Colin Sterling, 346–83. London: Open Humanities Press, 2020.

Deckha, Maneesha. “The Subhuman as a Cultural Agent of Violence.” Journal for Critical Animal Studies 8, no. 3 (2010): 28–51.

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom. Project Gutenberg, release date January 1995. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/202/202-h/202-h.htm.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

Haraway, Donna. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6, no. 1 (2015): 159–65. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919 -3615934.

Hyun, Insoo, Amy Wilkerson, and Josephine Johnston. “Embryology Policy: Revisit the Fourteen-Day Rule.” Nature 533 (2016): 169–71. https://www.nature.com/articles /533169a#/b7.

Ko, Aph, and Syl Ko. Aphro-Ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters. New York: Lantern Books, 2017.

Kymlicka, Will. “Human Rights without Human Supremacism.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 48, no. 6 (2018): 763–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00455091.2017.1386481.

Lumme, Hanna. “Tutkimus: Hennalan vankileirillä tapettiin mielivaltaisesti yli 200 naista— nuorimmat 14-vuotiaita.” 2016. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-8775599.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. “It’s Not the Anthropocene, It’s the White Supremacy Scene; or, The Geological Color Line.” In After Extinction, edited by Richard Grusin, 123–50. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Moore, Jason W. “The Capitalocene, Part I: On the Nature and Origins of Our Ecological Crisis.” Journal of Peasant Studies 44, no. 3 (2017): 594–630. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080 /03066150.2016.1235036.

Pekkalainen, Tuulikki. Susinartut ja pikku immet: Sisällöissodan tuntemattomat naiset. Helsinki: Tammi, 2011.

Shukin, Nicole. Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

iLumme, Tutkimus.

iiPekkalainen, Susinartut ja pikku immet. Ilmari Kianto’s text appeared in the newspaper Keskisuomalainen on April 4, 1918.

iiiSee Moore, “The Capitalocene”; Mirzoeff, “It’s Not the Anthropocene”; and Haraway, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene.”

ivAgamben, The Open.

vKymlicka, “Human Rights without Human Supremacism,” 764.

viKymlicka, “Human Rights without Human Supremacism,” 780.

viiHyun, Wilkerson, and Johnston, “Embryology Policy.”

viiiDeckha, “The Subhuman as a Cultural Agent of Violence,” 45.

ixColebrook, “The Future Is Already Deterritorialized,” 346.

x Colebrook, “The Future Is Already Deterritorialized,” 357.

xiColebrook, “The Future Is Already Deterritorialized,” 347.

xiiSee, for example, Butler, The Force of Nonviolence; Agamben, Homo Sacer; and Agamben, The Open.

xiiiBenjamin and Komlos, “The Purpose of a System Is What It Does.” The phrase was coined by the cybernetician and theorist Stafford Beer.

xivDeckha, 2010, 46 – 47.

xvKo and Ko, Aphro-Ism, 124.

xviKymlicka, “Human Rights without Human Supremacism,” 767.

xviiDeckha, “The Subhuman as a Cultural Agent of Violence,” 33.

xviiiShukin, Animal Capital, 7.

xixDouglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, 13. Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, 165.