Published on katoavamaisema.fi in accordance with the commissioned public installation, live stream based video landscape Katoava maisema / Disappearing Landscape, 2008.

A group of leaf trees in the front, twiggy bushes at the bottom of their thick trunks. The meadow is flourishing, lupins and young hogweed, a grass-green ditch stands out in the middle of all the purple and white. Behind the meadow where the colours of the flowers and the grass mix into a light, blotchy surface, towers a large tree. As the evening comes, the sun sets somewhere behind the field of pine trees looming behind the tree.

I try to adjust my camera, to find a good composition. I catch the clearing and half of the group of leaf trees but the picture turns out bleak, simple. I move the camera to the other side of the great spruce. Now the small birch saplings cover the entire picture again. After a moment of planning I seem to find the composition but I soon realise the effect is created by the lupins: in a month’s time the spot will be covered by grey-stemmed hogweed as tall as a man. And despite the fact that the mid-day sun is creating grand shadows now, in both the mornings and the evenings the spot is dimmed by the spruce. The view only settles into a picture if I choose a certain moment in time: even subtle changes destroy my aesthetic attempts. Yet it is the subtle changes that I am particularly keen to observe: the camera is to capture the view at a pace of 25 pictures a second for the next ten years.

The latest technology of its time

Over a hundred years earlier I.K. Inha, pioneer of Finnish landscape photography, photographed Finnish nature using a new innovation, a portable box camera. He journeyed for months through land both uninhabited and inhabited and captured its landscapes onto heavy glass negatives that would later form the main works of Inha’s production, books called Suomen maisemia (Landscapes of Finland) and Kalevalan laulumailta (From the Kalevala Song Country).

Although the camera Inha used represented the latest technology of his time, the inner aesthetics of the photographs reflect much older ideals. Photographs that display northern hills, untouched woodland and outback villages are joined with the canon of paintings that construct the Finnish national scenery.

The eye of the turn-of-the-Century artist sought the authentic, untouched Finland, a landscape that would not only depict the Finnish mindscape but also be useful as a metaphoric portrait of the newly-established state. Thus it was only natural that the depicters of the Finnish character would seek to the secluded places in the country, places that quite literally had never been seen before. The photography excursions that often turned out lasting months or even a year meant rides on trains as well as on horse-and- cart, endless hiking as well as sleeping in the wilderness. The traveler would be rewarded with a view from the top of a fjeld or a ridge or with a flash of everyday toil of the ordinary people. These images have since then become a part of Finland’s half-official portrait.

Like Inha, I too study landscape through the latest technology of my time: web cameras have developed rapidly and have rendered it possible to broadcast real time images online for everyone to view. My objective is to return to the authentic scenery and, in the urban Finland, open a window to the quiet life of the yearly cycle as it is experienced in the woods. And when I look at the pruned birch sapling stand and the tree field that surrounds it in all the four directions through the screen of my IP mega pixel camera, I feel that between myself and Inha, there is an inevitable path of a century from one to another.

INTERPRETATIONS OF THE EARLY PHOTOGRAPH

Traces of the past

The relationship of Inha and his contemporaries to photography was strongly coloured by the notion of the evidential value photographs held. Where the golden age painters created images of Finland onto a canvas using hand technique and sharp perception, Inha followed them and, in a way, validated their images. The idea of the evidential value of a photograph still echoes in the 1980’s in Roland Barthes’s definition according to which the essence of photograph can be found in its indexicality. Past the photograph itself, its meaning, the mark burned by light says: this has been. A photograph is proof of the passing of time to a viewer who thus gets his first direct look into the mirror of the past.

Yet the content of loss does not spring only from the reflection of a time gone past off a surface of a negative but also off the invisible shadow the photographer has cast on it. Up until the late 20th century a photograph always had a photographer, a person of flesh and blood, who carried out the deed of pressing the button. The objective did not capture the mere view but also repeated the picture drawn on the retina of the photographer’s own eye. A photograph was also evidence of the vanishing nature of a particular moment in life.

Naturally, our relationship to Inha’s pictures of the early 20th century Finland is coloured by nostalgia as they do, after all, even quite literally represent the lost world. Yet even Inha himself witnessed the rapid disappearance of the landscapes he had captured when he returned to the locations he once photographed. The last chapter, A Broken Melody, of his book Landscapes of Finland describes Inha’s journey on the already felled hills of Päijänne. ”That’s what it’s like now, the nature of our country. Where there isn’t death, there is a death sentence. The forest that our poets have sung about, for which our musicians have tuned their hymns, is in the past. The main lands are now broken, split and raped.” Inha writes: ”Where I still see primeval forest, I look at it with as much pity as I do with admiration.”

The presence of the end

The nostalgia of photographs is not only the glow of the past but also the close connection between the tool and death, the end of living time. The long exposure times that the early camera technology demanded favored still targets, and thus places such as graveyards were popular amongst the pioneers in the art. The same requirement also gave early portrait photography its death-mask-like effect as the models had to remain still for the ten minutes it took to take a photograph. It took a long time before technology was advanced enough to capture motion and therefore the first war reports, too, still depicted lifeless bodies in the aftermath of battles rather than actual battle scenes.

For Barthes, the essence of photographs does not spring from the aesthetic rules inherited from painting but from the ability of the photograph to verify something essential to a person about his mortality. A photograph, in a way, is a rehearsal of death, as the click of the shutter pushes a living moment into the books of the times gone past. Static and unchanging, a moment turns itself into negation, a monument of its own self.

REFLECTIONS OF THE OBJECTIVE IN THE LANDSCAPE

During Inha’s journeys at the turn of the 19th and the 20th century, natural science was rapidly developing new techniques for observing the world. Even as early as fifty years prior, early defenders of photography had predicted the daguerrotype to be nothing more than a kick-off for applications that would have vast consequences in all areas of life. In his essay ”A Small History of Photography” Walter Benjamin quotes his contemporary physician Arago’s defence speech to photograph: ”When inventors of a new instrument — – apply it to the observation of nature, what they expect of it always turns out to be a trifle compared with the succession of subsequent discoveries of which the instrument was theorigin.” However, fields such as astronomy or microbiology are also about observing the nature and their development is strongly linked to the development of optical equipment. Applications of the photograph have enabled mapping the world with unparalleled accuracy and thus also the vast harnessing of landscape to benefit human needs.

As the imaging techniques advanced, other kinds of nature relation techniques also developed. As Inha’s and his contemporaries’ nature photographs spread in the form of books, postcards and press photos for the urban dwellers to see, railways and the facsimile linked secluded parts of the country onto the same map. One no longer needed hiking trips, horse rides or guides in order to admire the wilderness; distance was no longer measured in steps but with the clarity of a picture or a sound, with the price of a train ticket or the hours of sitting the journey required. Simultaneously, urbanity spread to outback villages, bringing seeds of joint culture with it. It was only in photographs that the wilderness appeared unreachable and untouched anymore: outside the cropping, the landscape was already being introduced to dirt roads, felling clearings and telephone posts.

Thus it is no coincidence that outside the cropping of my own landscape image is a towering, giant radio telescope hidden underneath a white dome, as the settlement is barely behind the edge of the forest. The nature I am filming is a few-hectares-wide fragment between a tree field and settlement, only barely hidden from roads. The majority of Southern Finland’s patches of forest, meadows and groves that lay in between tree fields are overgrowing felling clearings or uncared-for fields, nature regaining its ground from people. My landscape, too, represents the type: it is a meadow inhabited by willowherb, hogweed, ash and alder. I have chosen the angle carefully but as much based on composition as for the sake of avoiding the pine trees that are under threat of regeneration felling as well as the alders that are to be de-branched. The authentic natural scenery now only exists in the aesthetic cropping of the picture, not at the actual location.

The impossibility of capturing untouched forest is not caused by the diminishing amount of wild nature alone. When in Inha’s day railways and facsimile systems spread over the country, now Finland is having a network of information technology built over it. The new technology infrastructure of today draws a new outback border on the map, the front line of wild nature: a line beyond which one can not yet see by opening a browser window. This project of real-time image and supervision technology that crosses state boundaries seems like a third stage of a plan to seize the landscape. Thus, alongside the advancing information technology, its nature observation applications – such as web cameras filming eagle nests or bear feeding spots – have also developed. These real-time images represent to our time what Inha’s did to his: a hidden view, a yet-untouched part of our country, authentic nature. Web cameras that observe natural phenomena can, in fact, be seen as carrying on in the same tradition of creating a paradise-like image of Finland that the golden age painters and photographers began. Now just like then a photograph links the possibilities offered by the advancing technology with the charm of the original world.

THE NEW PAINTING

Digital photo

As photographs were digitalised, debate over their truth value and the aesthetic principles guaranteeing truth has been revived. Digital photos are no longer based on a chemical process but on cells sensitive to light as well as noughts and ones. Thus digital photographs are, structurally, more information on the target than they are a material trace left by the target.

Media theoretician Lev Manovich suggests that the solid relationship between a photograph and reality has been nothing but a temporary exception in the history of the photograph. Manovich suggest that the notion of the causal relationship between the photograph and the reality that started in the early days of the photograph has been a misinterpretation, that has been advanced by the usefulness of the evidential value photographs hold when propping up dominant power structures. The evidential value associated with photographs is the very thing that has turned photographs into efficient tools of manipulation and targets of forgery. According to Manovich, digitalisation practically means that the photograph is returning to its roots, into one of the means of creating a fictional image. A photographer claims a status as an artist yet no longer as a second witness to a landscape but as a painter whose tools are digital image processing programs and staged scenes.

The last century has, however, left a lasting mark on the way we study photographs and their successors. A photograph is not merely a format but also a custom that has made strong ties with social structures. Digitalisation has turned photographs into hybrids in which facts and fiction are more characteristics of the form language than they are qualities of their essence. This grammar of the truth is what is under negotiation when a CNN reporter fixes the colour of the horizon in a picture he has taken or when a wildlife photographer joins two baby foxes into one picture. Thus, the contest for the rules of aesthetic rhetoric is always politically charged.

Automised image

The most touching quality of Inha’s production is its deep connection with the photographer’s personal experience. As the photographs are paired with travel journals, they gain verification of an intimate experience at the location. When Inha’s production that spreads over a period of more than three decades is paralleled with the photographer’s own personal history, it appears as a kind of a metaphor for life. Despite “the objectivism” of photographs, Inha’s production communicates a sincere intention to deliver his own experience of nature to the viewer.

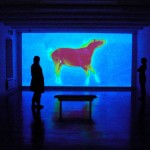

Sharing experiences is no longer a defining quality of the 21st century landscape photography. The presence of a photographer has more and more often been replaced by automatic functions that make it possible to place a camera in the depths of an ocean, high up in the sky, on the tips of missiles or on roadsides. The view that these pictures open up no longer repeats a human observation but produces other images from angles humans may never get to witness themselves. The sceneries in these pictures are no longer coloured by nostalgia. In a way the targets they show feel like they have in fact never existed anywhere else but as light reflected on the objective. The connection between a human, vanishing experience and a photograph has been cut off: the evidential value photographs hold is general demonstration, separated from the existentially charged experience that Barthes used to define a photograph. ”This has been”, a modern image appears to be saying, but not to someone, sometime, experienced by somebody but instead generally. The view no longer marks a place that can be experienced in space – it is a mere image, nothing else.

Real-time image

Analogical film technology is based on recording individual photographs and repeating them chronologically. The movie technique based on the exposure of images carries the same nostalgia in its technology that Barthes experiences when looking at a winter garden photograph. It is just as much about physicality as it is about distance in time between taking the picture and viewing it: ”this has been” supports the stream of pictures running before the viewer’s eyes.

If digitalisation has questioned the interpretation of photograph as a trace, real-time image streaming has caught up the distance in the time of taking a photo and viewing it. We have moved from past-fetishism to now-fetishism: the punctum of a camera image no longer is this has been but, rather, this is. Like windows opening up to other places, web camera projects, property security systems and news image streams all together repeat the simultaneous mass of events in the world: here before you, out of reach, this is.

Real-time video image can be seen as an attempt to restore the evidential value of the photograph, its direct relation to nature. The authenticity of real-time video image is based on minimising the distance in time and thus on minimising the staging and manipulation of events. The focus of real-time films has shifted from static pictures to action in the image. Authentic no longer refers to authentic scenes but authentic deeds. Therefore it is no wonder that interfering with bodies produces the most repeated motifs in the image industry. One can only act pain and pleasure to a certain point: the most authentic of all authentic deeds is the very death of a body. And thus the most authentic of all landscapes is the very one that is disappearing before our very eyes. The appliance itself has taken the vanishing place from which Inha, in his time, viewed the landscape.

Like analogical film, a real-time film is formed of single images that are displayed in a chronological order. Each individual image holds the entire history of photography, its interpretations, its practices, nostalgia and relation to the lifeless. As a view turns into an image as in direct observation, it is as if the image of death had caught up with the present, burned onto its surface. Here before you, out of reach, this is already over. What is left is the experience of viewing, the living moment of witnessing. Perhaps real-time photos are indeed related to theatre but not so much in the meaning of the death cult as sketched by Roland Barthes. Rather, it is more about the theatrical aspect that Michael Fried connected with minimalistic viewing of art: experiencing a piece becomes theatricalisation of the viewer’s body and consciousness.

EPILOGUE: DUAL EXPOSURE

The lupins wither away and green and white hogweed take over the ground. The sky is darker than during the spring-time test shoots and the sun now sets before it even reaches the inside of my framed image. The light will inevitably lessen, in the winter my picture will only paint shades of black and grey.

My landscape is not rugged, not even particularly beautiful, unlike the sceneries photographed by Inha. Those views are gone, just like Inha himself, out of the reach of cameras. My pictures display a perfectly ordinary Southern Finnish forest meadow, a modest, even wood of small detail between settlement and commercial forest. But it feels like Inha’s landscape, in a way, is outlining from behind of mine.

***

This photo, too, will disappear – in many a way. It will vanish from the viewers’ experience that moves in the stream of living time, unrepeated. But it will also actually disappear: first its technology, cables, appliances and cameras will weaken. Then the landscape itself will disappear, either through the natural cycle or, what’s more likely, as consequence of construction. But some time even the eye that has viewed the scenery on an LCD monitor will disappear as will the building around the monitor and, eventually, the entire city. And perhaps one day a real forest will grow through the site of the image.