Authors: Laura Gustafsson and Terike Haapoja

An introductory essay in History According to Cattle (Into Kustannus, punctum books, 2015).

The assumption that language constitutes the defining foundation of human experience came to govern popular conceptions of humanity in the 20th century. The countless realms of non-human experience outside the hermetic realm of human language were thus consigned to silence. Animals were relegated to muteness, voicelessness and linguistic Otherness, denied access to all forms of negotiative discourse. As a result, a problematical attitude of scepticism has pervaded the animal rights debate for the past century. If we cannot say anything valid about how animals feel, it must hence be impossible for us to prove or disprove whether or not they feel at all. Contrary to the tenets of the western justice system – where the accused is held innocent until proven guilty – our ongoing exploitation of animals is paradoxically legitimated by our very inability to bear witness to their suffering.

The notion of human language as the all-embracing foundation of our reality has likewise entrenched itself in western art. Whenever an animal viewpoint is expressed in words, whether in literature or theatre, it invariably comes across as an invitation to naïve anthropomorphism, the animal being reduced to a mere figment of the human imagination. Typically, animal-themed art is in fact visual, as if to suggest that animals can be taken seriously only as images – and, thus, only as mirror images of humans. In the light of recent ethological research and critical animal studies, however, the discursive relation between language and animals is no longer as unequivocal as it once appeared to be. Agricultural exploitation, species extinction and the ensuing crisis in the status of fauna have forced us to rethink the extent to which we can connect and interact with animals. Language is a challenge, but the obstacle should not be insurmountable.

The anthropologist Eduardo Kohn coined the term “ontological autism” in reference to the Runa people of Amazonian Ecuador, who communicate with their hunting dogs to help both the hunter and dog connect on a sensory level with their prey. This human-animal connection is fundamentally an issue of survival, as both hunter and prey must be able to anticipate one another’s next moves. The ability to think like the Other is critical to these tribespeople who are dependent on each other and on nature for their survival. To them it is self-evident that their fellow creatures have their own subjective will, intent and sensory reality. “Ontological autism” describes a state in which a tribe member, hunting dog or beast of prey loses the ability to anticipate the intentions of their fellow creatures, whether as the result of a curse or magic. The tribe regards this state as a fatal danger.

Ontological autism – the condition of perceiving the world and its creatures as mere objects without a subjective inner reality – can be diagnosed as the human condition that has prevailed since the agricultural revolution, which trivialized our need for two-way interaction with nature and our fellow creatures. If we perceive our surrounding reality as nothing but an exploitable resource, why bother to make any effort to understand how others might feel, much less relate to livestock as intentional subjects? Harnessing art to imaginatively identify and empathize with animals might offer an escape route from our current condition of autism.

The motivation for The History of Others project is that history has traditionally been written from the viewpoint of only one species: humans. The narratives fed to us by museums and history books reinforce the myth of the human race on a steady march toward ever-higher peaks of progress, tomorrow always better than yesterday. Human-written history is the history of humankind as a victory over other species. But how might history look through the eyes of a non-human species – a species that has played its own contributory role alongside the human race in the unfolding plot that we call history? Only in recent years have scholars in various fields of the humanities taken an interest in exploring non-human perspectives on our shared reality.

‘Encyclopaedic’ is a term that aptly describes The History of Others, which boldly aspires to reinscribe the entire spectrum of known history and recognized species. If only by virtue of its sheer improbable scale, it foregrounds the colossal blind spots of human-written history. The History of Others is not purely conceptual, however: it aspires to create tangible, museum-like spaces documenting the history and experiences of non-human species. Writing is by definition implicit in the very concept of history, which is defined as beginning when humankind first began recording speech in written symbols around 3,600 BCE (albeit the very earliest system of ancient writing dates back to 7,000 BCE). Writing evolved with the transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies. An instrumental role was played in this historic shift by domesticated livestock, particularly oxen, who ploughed the fields and fertilized the soil. Without them, agriculture – and hence the birth of history – would not have been possible. In light of the debt that history owes them, cattle were the obvious choice as the first non-human species featured in The History of Others project.

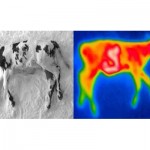

The realization of a Museum of the History of Cattle nevertheless presented a fundamental challenge: creatures without any tradition of recorded language cannot have a ‘history’ in the conventional sense. A Museum of the History of Cattle was therefore a paradox in terms. We had two alternatives: either to force the innately non-linguistic mode of existence of cattle into the mould of human linguistic expression or to dispense with language altogether.

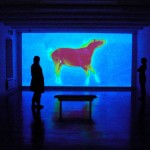

The latter alternative would have permitted deeper penetration into the experiential domain of cattle – its odours, colours and the industrial contexts that define the existence of livestock – but this would have erased the historical perspective. Language is the vehicle that allows us to transcend the temporally-bound subject. Without writing, the Museum of the History of the Cattle would merely have been a re-enactment of a here-and-now contextual experience of reality. Admittedly this might have said something about how cattle perceive time: perhaps their notion of time is not linear as we westerners presume it to be. But such a hermetic interpretation would have made it all the more difficult to comprehend reality as it is experienced by cattle and the contexts in which they have existed throughout history.

The use of writing also helped us avoid the object-centricity that is typical of museums, an institution that evolved with the rise of bourgeois consumerist culture. The early treasures displayed in curiosity cabinets celebrated the new trade opportunities that were opened up by seafaring and scientific expeditions to foreign lands, thus inseparably linking these artefacts with the history of global capitalism. Even today, artefacts still occupy a focal role in nearly all modern museums of cultural history. The narratives engendered by the dominant bourgeois-capitalist worldview thus treat history as a history of objects, even when those ‘objects’ once happened to be living creatures. Museums of natural history relegate taxidermied animals to the status of artefacts, closer to consumer goods than active agents in their natural habitats. An object displayed in a museum is nothing more than its exterior purports to be. Saying nothing about itself, it is merely a symbol representing a wider taxonomy of objects, cultures or customs. The erasure of the background story and context are symptomatic of object-centric museology, which shares nothing about the wordless culture of gestures, experiences, feelings and subjectivities. The objectified taxidermied animals that we see displayed in museum cabinets are doomed to silence, revealing nothing about themselves or their subjective world.

The Museum of the History of Cattle is not only about livestock, but also about history and the museum institution overall. By subversively borrowing the conventions of traditional museums of cultural history, it questions existing codes of recording history and their inherent anthropocentric bias. The Museum of the History of Cattle inverts the customary object-narrative relationship that is perpetuated by traditional museums. A generous amount of text is provided, yet very little background information is shared about the few objects that are on display; instead, it is the story around them that is emphasized. Rather than focusing on objects, the museum foregrounds what is normally erased: the context.

The written word nevertheless posed a problem: how could we write from the viewpoint of an animal whose experience is completely alien to us, a creature unable to communicate in human language, much less in writing, a creature with no tradition of recorded history and therefore no notion of subject-transcending historicity. It was not, however, our intention to present an authentic document of the world as it is perceived by cattle. Although we share many basic experiences with other species, abstract linguistic expression is, as far as we know, a uniquely human aptitude – yet language still remains hopelessly inadequate at conveying anything about corporeality or corporeal experience. Language nevertheless provides the human species with a mental toolkit for making sense of the world; ideally it can serve as a bridge to the experiential realm of the Other.

Contrary to what is implied by the seemingly objective language often used in museum displays, language is never neutral. The Museum of the History of Cattle uses a variety of different linguistic registers rather than presuming the dominance of any particular mode of discourse. Irony, humour and lyricism by turns shed light on the potent meanings with which words are charged. By making visible all that is normally concealed, the museum makes a statement about the modes of discourse conventionally employed by history writers and museums. Rather than suggesting that the Museum of the History of Cattle is a mouthpiece for oxen, it extends an invitation for people to rethink their concept of humanity by transcending the confines of standard history-writing. The cattle provide a mask for us to imagine human beings in a wholly new light. We may not be able to vicariously re-experience how cattle see the world, but we can at least distance ourselves from our normative perceptions of our fellow human beings and other animals.

The Museum of the History of Cattle considers the historical conditions that have defined the existence of livestock for the past ten thousand years, namely their interaction with human civilization and human society’s attitude toward non-human species. It eschews the logic of the natural sciences and agriculture, which classify domestic animals solely in terms of their exploitative potential, but without taking a stand on animal rights issues. By disavowing the conventions of both extremes of the discursive spectrum, the museum brings to light a bovine point of view, while at the same time engaging in a ludic play on linguistic conventions.

Expressing the viewpoint of an animal in a work of art can, if not bridge, then at least question the gap between us and the Other, whilst at the same time embracing an acceptance of the deficiencies inherent to the chosen methodology. Art is self-reflexive, invariably exposing the inherent subjectivity of its chosen medium. Whenever art says something, it simultaneously questions what is being said and how it is said. Art even uses language to expose its own limitations, quietly making space for what is normally excluded from the linguistic realm. The Museum of the History of Cattle is both a museum and a fragment of history-writing, debunking the conventions of museology and history-writing, and exploring how and why these conventions are upheld and to what ends they might be exploited.

Science and other institutions widely attributed with social credibility obey their respective linguistic codes and methodologies. In the discourse of science, economics, politics, academia and law, it would be quite a feat to prove that the viewpoint of the Other exists in the first place, much less that it might be relevant or worthy of our consideration. Official discourses purport to represent a neutral standpoint, as if they encapsulated an incontrovertible truth free of ideological baggage.

Art denies any claims to universal truth by self-reflexively exposing its own discursive mechanisms. In doing so, it debunks the assumption that there is any such thing as a univocal truth in the first place. In a world that rewards the pursuit of personal gain, such honesty is no doubt regarded by many as tantamount to insanity. One of the greatest merits of seemingly absurd projects is their ability to unmask moral codes and the elites who extract the greatest gain from prevailing belief systems. The only way to break free from fossilized modes of thought is to acknowledge that they exist in the first place.

We cannot know how the world might look and feel from a bovine viewpoint. We cannot authentically replicate the experience of cattle. We can, however, acknowledge that such a viewpoint and alternative mode of experience exists. It is the duty of art to expose our blind spots. Although we can only remotely imagine what lies buried behind them, the mere act of acknowledging their existence is important in a world where ideologies – economic doctrines in particular – seek to systematically deny and render them invisible. The Museum of the History of Cattle is a reflector; for a fleeting moment, it transforms our surrounding reality into a context that celebrates the bovine viewpoint as a valid part of our shared experience of reality. It thus endeavours to alter not only how we understand history, but also the present and future.

This volume aims to open up a space for a broader contextualization of the themes presented in the related exhibition project. Art historian Anne Aurasmaa gives us an insight into the history of the museum institution and the issues relevant in today’s museological practice. Although museums are often considered to be unbiased and objective, Aurasmaa reminds us that the museum is a western construct with pronounced colonial and anthropocentric traits.

The philosopher Elisa Aaltola investigates the role of language in our perceptions of other animals. Aaltola shows how the traditions of Cartesian philosophy and linguistics, which place propositional language at the basis of consciousness, have prevented humans from acknowledging animal minds and from communicating with other species. As Aaltola says: “There is a world before and beyond language, and a mind capable of grasping it without the use of propositionality.”

“Bad faith” (mauvaise foi) is a concept from existentialist philosophy. According to existentialism, an individual is fundamentally free to make choices, no matter what situation they are in. When acting in bad faith, individuals fool themselves into believing there is no choice, thus reducing themselves from free agents to mere objects. The theorist Kris Forkasiewicz uses the term to describe how humans have adopted the concept of the animal as something inferior to humans, and how rejecting their animal features leads humans also to deny a great part of their bodily selves.

Providing some details on a subject too big to cover in the exhibition, curator and researcher Radhika Subramaniam writes about the role of cattle on the political scene in India, and about the ways in which they are co-opted into religious nationalism. Subramaniam’s essay helps explain the high death rates of cattle in India, something that we might find odd in the light of the powerful myth of the sacred cow that comes up when we think of India.

***

Translated from Finnish by Silja Kudel.