The Party of Others

Launch of a political initiative and exhibition

Gallery Kalhama & Piippo Contemporary

Helsinki 2011

The Party of Others is structured around interviews of leading local thinkers from the fields of animal rights, environmentalism, law theory, art and politics. The interviews focus on two key questions: what would a society that would not be based on exclusion be like? What would the structure of governance be in a society that would include everybody that was present, the nonhuman world included? The interviewees are asked to replace the words “animal” or “nature” with a species neutral term “them”. The resulting recording reveals how the discourse on rights of nature is in many ways identical to any rights discourse in the past, and also how even in that discourse, access to propositional language forms the ultimate boundary of a political community.

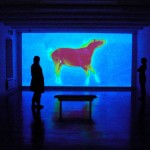

In the first exhibit of the project (Helsinki 2011) the edited and musically composed interviews were audible each from their individual speaker that together formed a choir of chatter around the questions of “what to do with them” and “what would they want”. A large scale 3-channel video projection showed in text animation how certain themes and initiatives from the interviews formed patterns of consensus and disagreement: the subjective, uncertain chatters of the interviews transform gradually into political facts and ideological programs.

Further, the project reached out to the world, developing into an initiative for a real political party that would reflect the ideas presented in the interviews. The party platform of the utopian Party of Others, based on the interviews, shows an attempt to fit the radical, utopian ideas of a truly open society, which would not be based on exclusion, into a traditional political party strategy. In the impossibility to do so, the limits of our anthropocentric representational democracy becomes tangible.

The resulting agenda includes detailed notions of community, law, language, imagination, education, representational structures and altruism. It is radical in the sense that it calls for a fundamental change in the society on all levels, from culture to power structures. But the agenda is also realistic, as there are many proposals for improving the status of the excluded that could be realized already inside the existing political structure.

In order for an association to establish itself as an official political party in Finland it needs to collect 5000 signed support forms from voters. After the registration, the new political party has two years’ time to run for seats in the parliament, after which it drops out of the official register.

The project was launched with a campaign for registering the party into the official party register. The Party of Others project received great amount of interest and a lot of media coverage, though not enough supporters to register the party. Since 2011 The Party of Others exists as an extra-parliamentary initiative that can be used for raising discussion on the voice of the voiceless and on the margins of our democracy.

Working group for the exhibition

Video assistant: Ewa Gorzyna

Sound assistant: Joe Candido

Programming: Gregoire Rousseau

Producer: Piritta Puhto

Interviews, Helsinki 2011

Elisa Aaltola, philosopher, Yrjö Haila, professor of environmental politics, Tampere University, Kristo Muurimaa, activist, Aleksi Neuvonen, philosopher, researcher, Antti Nylèn, author, essayist, Markku Oksanen, academy researcher, Turku University, Leo Stranius, head of Luonto-liitto, Joonia Streng, lawyer, Jarkko Tontti, poet, lawyer, Salla Tuomivaara, sosiologist, head of Animalia, Leena Vilkka, Phd environmental philosophy, Birgitta Wahlberg, researcher, Åbo Academi

Selected quotes from interviews (translated from Finnish by TH)

Birgitta Walhberg

Researcher, Åbo Academi University

Phd on Legislation and Supervision of the Welfare of Farm and Slaughter Animals.

“I think it’s interesting that when we talk about their juridical rights, it’s mostly humanists and philosophers who take part in that conversation, not so much legal scholars. Legal scholars tend to comment only, in a top down manner, on why it is not possible that they could have rights. And the legal scholar’s opinions are often based on certain logic of existing legal theory, while they don’t tend to take part in the conversation about how we could change that theory, or whether it’s needed or important from their (nonhumans) perspective to change laws.”

“What I see as problematic in the current legislation is that they are seen merely as objects of protection. They are seen as objects with no inherent value. And this notion of them as objects is what underlies our interpretations of law and how it’s applied – objects, that we protect and whose wellbeing we try to improve. If it was possible to include a notion of their intrinsic value in our legislation, that they would have intrinsic value as individuals….to expand the current notion of protection of the individual to include a notion of the individual’s intrinsic value. That would turn the whole approach of law and it’s interpretation and the way it’s applied toward acknowledging their needs.”

“Historically, when the question of women’s rights emerged, one counter argument was that we women’s rights aren’t compatible with the language and concepts of law. Now we are facing similar arguments about whether they could have rights and how that would fit our legal concepts and the apparatus of law in general. To acknowledge their legal rights would definitely require a completely different set of concepts and a radical reorganization of legal systems in order to be able to process them in courts and official proceedings.”

“In a way I see the claim that they should have rights also as a possessive gesture from our part. Who are we to say or define what their rights are. Just by demanding rights for them we are subjecting them to our world and it’s rules. But if we talk about intrinsic value instead, then it’s possible to have a conversation about them having their value, us having ours, and that we should respect them because they are in a weaker position in the world than us.”

Leena Vilkka

philosopher

author of The Intrinsic value of Nature

“I personally have a strong belief in that it is the environment that defines what the community is – that the environment comes first. The environment gives us the framework and the conditions that determine what we, humans and all the other species, become. In a way we don’t have any other option than to adjust to the conditions that are given by our environment. It determines everything in our lives. Gives all the possibilities and options. And the widest notion of an environment is of course the earth, that is actually a really miraculous place: we look to the sky and see all the stars, the suns, planets that are lifeless, so it’s really a miracle that we are living as part of this planet of life.”

“If you think of the origins of rights, in the Greek philosophy 2000 years ago it was only white men who had rights, while women, children, the enslaved were all those “others” that were outside rights. One could say that we’ve lived through an expansion of the field of rights. In the end of the 19th century women, workers, the enslaved started to demand rights – or actually not even these groups themselves, but progressive white men who started to demand rights for these groups. And it is telling that the demand for women’s rights was countered by ridicule, that if we give in to these claims, soon they’ll start demanding rights for beasts too. And one can say that in a way this fear, this prediction, is reality today”.

“The one right that they lack is the most fundamental right, the mother of all rights, which is the right to life. So we can say that if we don’t have a right to life, then do we have anything really. And this right is lacking from everyone else than humans. One could say that its just three small words: right to life. And when this claim is made to include animals, plants, trees, it becomes a very strong political, societal claim. It is a strong claim to really expand and change the whole foundation of the western society.”

“[in order to have a political community in which they would be heard] We should have more sensitive ears to hear them. One can say that at this very moment only a small group of people are heard in decision making processes, that most of us are voiceless or have a very limited or quiet voice, or who in practice have very limited access to decisions that regard them, besides maybe their own everyday life issues. So we are talking about power really. And few have it, and then it becomes a question of how those who have power use it and who do they hear. Do those in power hear or take into account the rights and well being of nonhuman beings or ecosystems. “

“They could have their own legal representatives that would represent them, the same way that we have lawyers. We could have nature-animal lawyers, whose job was to advance their rights and bring their cases forward in the legal system, if there were situations where their rights were injured.”

“I don’t think that lack of knowledge is the first and foremost problem, but mostly lack of will and whether they are acknowledged or left out. I think it can be said that we do know what they want, that’s not the question. They need to be left alone, they need space to flourish, they need the sun, they need nourishment, space to move. We have enough knowledge about what makes them happy. The question is whether we grant them the right to exist”.

“Our whole political system is anthropocentric. It is built around talking about human affairs. We talk about other people’s issues, of issues regarding different groups of humans, or children or elderly people. It would require a big change in the political climate that we’d talk more about the future in general, the needs of future generations. That we’d scale down the anthropocentrism of political thought and then expand it so that it could include first those nonhumans that live close to us and are sentient, conscious beings. To take their needs into account, expand our thinking to a zoocentric thinking, where their needs are on the same level of importance as ours. And then of course the next step would be to expand the ethical field toward zoe-centric approach, where humans aren’t the center point and focus of everything, but on the same level with everything else.

“My utopian society would consists of ecological cities, ecological rural areas, greenlands. It would be based on a view of a future in which there was no meat eating, that food production was based solely on ecological farming, ecological organic farming, so food was mostly plant based. Maybe in a land of a million lakes like Finland it could be partly fish too. It would be based on local farming, local energy production, sustainability – all which is very far from the world that we live in at the moment.”

“We are going towards ecological catastrophies, environmental crises, the earth simply doesn’t tolerate the actions of humans and then we arrive on the fundamental issue of population growth: theres simply too many of us on the planet. That’s surely one of the taboos of our times, that isn’t really talked about. But I think it will be a critical question. That there’s simply too many people at this moment. (…) I see women’s rights deeply connected to this issue: it is well known that the more educated women are, the later they give birth and have less children. That’s why I don’t see a big conflict between women’s rights and rights of nature. Our world has traditionally been dominated by the power of one gender, that has then defined both women’s role in the society and the rights of nonhumans.”

“I think we should look at indigenous people’s cultures, that have traditionally had a strong relationship with the nonhuman world. We can communicate with the nonhuman world if we desire to. Many indigenous people have had an organic connection to the environment and acknowledgement of the fact that not all valuable knowledge is not produced by human minds. One can ask advice from nonhumans of weather, other natural phenomenon, the future. The nonhumans can be advisors. For example in Sámi culture there are shamans that have the ability to communicate with the nonhuman world, to ask an eagle or wolf or bear. To seek knowledge from these animals, because it’s been acknowledged that human knowledge is limited and they know more. In our world the starting point tends to be that all human knowledge is important and precious and nonhumans could not possibly possess any kind of knowledge that is valuable. In that I think we need a new kind of ecological sensitivity in order to start listening to what the nonhuman world has to tell us. In fact they are speaking to us all the time, but their speech reaches us as these peaks, eco-catastrophies, in the form of storms and destruction and climate change, because we haven’t heard their more subtle speech. We are getting feedback from the environment all the time. We get it as polluted food or toxic, unlivable land and that speech we hear. But we haven’t heard them telling us how we could live in this world in collaboration, in a community, before these crises that we’ve created come to us.

Leo Stranius

City Council member (Green Party)

long time environmental activist

“At this moment the problem is exactly in that they have no basic rights at all. They don’t have a voice in decision making nor there is any article in the current legislation on how the voice of the silent would be heard. And by the silent or voiceless I mean animals and the environment but also future generations. Perhaps our decision making processes should be built around the benefit for the weakest and least capable in the society. And if we think who is, in the current society, in the weakest position, they are usually those who’re voice is not at all heard.”

“We’d probably need both direct means of communication with those of them, with whom we can access into dialogue, and then there are for sure some groups that would need a representative. I don’t think there’s anything mystic about us being able to communicate with them directly, because we are doing it all the time when we are making decisions. Let’s say that the Ministry of Agriculture grants hunting permits, that is the most direct communication with the wolves, with those who are not able to participate in the process that regards them.“

“ I find myself to be always an optimist – I believe that this will happen bit by bit. Just like we’ve seen that the ethical sphere has widened to include more and more groups of people, and gradually to nonhumans, the environment, future generations. This is how it expands: in the previous centuries it was beyond imagining that you couldn’t use slave labor, and today hardly anyone is saying out loud that we loose our market value if we can’t use child- or slave labor. So we are able to take for instance the interests of children into account even if they are not voters in the current system. So it is absolutely possible to expand the ethical field and I think this will happen too.”

“For them to have basic rights would lead to dramatic changes in our society on the long run. Probably this wouldn’t happen through a major revolution or dramatic event, but through small steps of advancing our understanding and acknowledgement of different interests. But as a practical result this could for example lead to reducing carbon emissions to close to zero, stop overconsumption of natural resources, which would stop the loss of biodiversity. We would adjust our ways of life to the context where natural resources are limited and other species are not exploited and in general our well being was not dependent on oppressing and exploiting them.

“One good criteria could be that it was necessary to talk on behalf of the other as a basic rule of decision making. So in a way everybody would represent different approaches, but the only criteria was that you are not allowed to represent your own interests. If you would do that you would be dismissed. But of course if we represent their interests, we also represent the interests of ourselves at the same time. Another principle to consider could be the notion of the last person, where we would take the least powerful in the community as the starting point and made sure that our decisions and actions would specifically improve the situation of that individual or being. Also others, but them first and foremost, because the team is only as good as it’s weakest link. And in this case the weakest link is obviously not the last human but the last of them, the last animal, the last forest.”

“It’s not so much about giving up things than it is about receiving. How could a Party of Others bring this question up in the light that this is not about giving up things or withdrawing, but that the more we give to the others and withdraw and divest from something we don’t really even need, we are getting something so much better in return. It’s also about the fact that we’re living with a limited capacity. The more we can give well being to others, the more we can receive it ourselves.”