Julkaistu: AVEK-lehti 2/2013

Eronteon strategioita

Marginaali-argumentti on filosofinen argumentti, joka on keskeinen eläinoikeusteorian piirissä käydyssä keskustelussa. Argumentti kyseenalaistaa eläinten ja ihmisten erilaisen kohtelun oletettuun lajityypilliseen piirteeseen, kuten ihmisen tietoisuuteen tai itsereflektioon perustuen. Jos pidämme tietoisuutta moraalisen arvon perustana, voimme aina löytää marginaalisen joukon ihmisiä, joilla tätä piirrettä ei ole. Kuitenkin myös näitä henkilöitä kohdellaan moraalisen arvon omaavina. Jos siis vastasyntyneillä, vaikeasti vammaisilla tai koomapotilailla on moraalinen arvo, ei tulisi olla estettä ajatella myös toislajisia eläimiä moraalista arvoa omaavana. Vastaavasti on aina löydettävissä toislajisia eläimiä jotka kykenevät toimintaan, jota pidetään ihmistä moraalisesti muista lajeista erottavana, kuten työkalujen valmistamiseen, kielen käyttöön, kulttuurin siirtämiseen jälkipolville tai mielen teoriaan.

Argumentin tähtäimessä on kulttuurillemme keskeinen tapa yrittää loogisesti perustella ihmisen ja muiden lajien välistä erontekoa ja näiden erilaista kohtelua. Ihmisen muista erottavaksi erityispiirteeksi ja erityisen moraalisen arvon takeeksi on ehdotettu milloin sielun, milloin järjen olemassaoloa, kykyä propositionaaliseen kieleen tai sosiaalisten suhteiden solmimiseen. Yksi kerrallaan nämä erityispiirteet on löydetty myös muiden lajien tapakirjosta, ja yksi kerrallaan on nostettu esiin uusia ihmisen erityispiirteitä. Ongelmana on, että ihmisen ja muiden lajien marginaaleissa tapahtuu ominaisuuksien sekoittumista, joka tekee mahdottomaksi kategorisesti erottaa yhden lajin kykyjä toisen lajin kyvyistä. Eläinoikeusfilosofi Peter Singeriä mukaillen: mikään kaikille ihmisille yhteinen piirre ei kuulu vain ja ainoastaan ihmiselle: esimerkiksi kaikki ihmiset, mutta myös muut lajit, pystyvät tuntemaan kipua. Vastaavasti vaikka vain ihminen kykenee ratkaisemaan matemaattisia ongelmia löytyy aina ihmisiä, jotka eivät siihen pysty. Kategorinen eronteko ihmisen ja muiden lajien välillä on perusteeton, ja siten myös erilaisilla moraalisilla kategorioilla ei pitäisi olla perustetta. Kuitenkin nuo kategoriat ovat todellisuutta.

Yhteiskunnan hiljainen perusta

On kiinnostavaa, että rajanvedon logiikka kaatuu juuri ihmislajin marginaalissa, olemmehan tottuneet ajattelemaan eläinkysymyksen poliittisen keskustelun laitamille. Eläinkysymyksen valossa kuitenkin ihminen kategorioineen on marginaalissa, tai oikeastaan lähinnä marginaalien ihmisellä on merkitystä. Eläin itse on kaikkea muuta kuin marginaalinen, sillä se edustaa huomattavaa enemmistöä yhteiskuntamme jäsenistä. Toislajiset eläimet ovat yhteiskuntamme suuri massa, jossa jokaista ihmistä kohti on tuhansia toisia. Tämä hiljainen massa ei puhu eikä vaadi oikeuksiaan, ei tee jaotteluja eikä osallistu moraalifilosofisiin keskusteluihin, ja silti se ylläpitää yhteiskuntamme perustavia toimintoja ruoantuotannosta maaduttamiseen ja ravinteiden kuljetuksesta pölyttämiseen. Ilman näitä me emme söisi, joisi, emme tekisi taloutta emmekä politiikkaa.

Emme helposti ajattele toisten lajien jäsenten kuuluvan yhteisöömme. He ovat pikemminkin perusta, alateksti, jonka varassa kaikki lepää, mutta jonka osallisuutta ei tarvitse huomata. Yhteisö on jotakin muuta: yhteisö on toiminta, joka muokkaa perustaa ja päättää sen puolesta. Vain vapaat ihmiset ovat voineet muodostaa yhteisön, joka haastaa hallitsijan ja muodostaa kansansuvereniteetin, jolle hallitsija on alamainen. Suvereeni valtio on kansan, ja kansa taas poliittiseen pystyvien yksilöiden summa. Kansanvalta tarvitsee hiljaisesta perustasta irti nousseiden toimijoiden joukon, joka artikuloi kansan tahdon. Keskeiseksi nousee tapa, jolla perustasta erottautuminen tapahtuu. Tuo vaiennettu perusta ei aina ole ollut ei-inhimillinen. Siihen ovat kuuluneet niin orjat, naiset, vammaiset kuin lapsetkin. Vapaustaistelu kerrallaan nämä ryhmät ovat vaatineet oikeutta kuulua yhteisöön, ja kukin myös saaneet oikeutensa ja vapautensa. Oikeuden perusteena he ovat käyttäneet juuri ihmisyyttään: juuri ihmisinä he kuuluvat yhteisöön ja osaksi poliittista. Näin valtio itsessään syntyy essentialismin perustalle, erontekona ei-ihmiseen, josta erottautuneet ihmisyksilöt voivat muodostaa poliittisen yhteisön.

Eläinkysymys ei muodostakaan vain yhtä erityistapausta diskriminaation historiassa, orjien, naisten ja lasten seuraajaa. Eläin ei ole yksi esimerkki ”sorrettujen” tai ”ulossuljettujen” kategoriassa, vaan eläin itse muodostaa tuon kategorian. Koska on olemassa eläin, tuo ei-ihminen, on ihmisten muodostama valtio mahdollinen. Ei ole vain sattuma, tai perinteikäs haukkuma, että syrjityt ihmisryhmät leimataan eläimiksi. Uhka on todellinen. Niin kauan kun valtio, poliittiinen yhteisö, perustuu ihmisen ja ei-ihmisen väliseen erontekoon, on kenet tahansa mahdollista sulkea valtion ja oikeuden ulkopuolelle ja sallia häntä kohdeltavan ”kuin eläintä”. Paradoksi on, että juuri eläimen toiseksi tuottava oikeusvaltio ja sen suomat pakkovallan keinot ovat niitä, jotka voivat toisia lajeja ihmiseltä suojella.

Eläimen kadottaminen

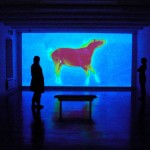

Eläimen samanaikainen lisääntyminen ja poissaolo leimaa modernia aikakautta. Ihmisen kadotessa kaupunkeihin ja toisten lajien kadotessa tuotantolaitoksiin ja maaseuduksi erotettuun maisemaan ihmisen välitön suhde toisiin lajeihin muuttui. Eläin ei enää ole kanssaeläjä, jonka osallisuuteen olisi luotava päivittäinen, toimiva suhde. Eläin on teoreettinen, abstrakti, ongelma tai käyttövara. Nykykulttuurissa eläin on yhä vähemmän todellinen yksilö ja yhä enemmän merkki, jolla on merkitystä vain ihmisen maailmassa, osana tatuointien, vaatekuosien ja kielellisten ilmausten kehystä. Näin eläimen taikavoimat on siirretty ja otettu osaksi ihmisen maailmaa. Yhteiskunnan toisella laidalla eläin palautetaan puhtaaksi materiaaliksi, turkiksi, lihaksi ja nuggeteiksi, jonka arvo tulee vain sen käyttö- ja nautintoarvosta ihmiselle. Samassa (teollisessa) prosessissa eläimestä on hyödynnetty sekä sen merkitys että sen ruumis. Eläimen katoamista siivittää eläimen tuottaminen uudestaan monistettavassa muodossa. Sekä symbolisen että materiaalisen eläimen pääluvut ovat moninkertaistuneet miljooniin tai miljardeihin: pelkästään nautakarjaa elää planeetalla yli miljardi yksilöä, eikä susitatuointien tai leopardikuosien määrille ole luokitusta.

Kun tieteellinen tieto kyseenalaistaa ihmisen ja eläimen erilaisen kohtelun olemukselliseen eroon perustuen on pääteltävä, että eronteko on käytännöllinen ja liittyy valtaan. ”Eläimen” kategorian olemassaolo hyödyttää niitä, jotka ovat vallassa. Mitenkään muutoin ei voi selittää tuon kategorian sinnikästä kestävyyttä vedenpitävistä teoreettisista, tieteellisistä ja moraalisista argumenteista huolimatta. Koska raja ihmisen ja eläimen välillä hyödyttää ihmistä, ei sitä ole varaa purkaa. Argumentit siirtävät rajaa mutta eivät murra sitä. Ympäristökriisi kuitenkin kyseenalaistaa lyhytnäköisen taloudellisen intressin ajamaa politiikkaa ehkä laajemmin kuin koskaan aiemmin. ”Hyödyn” käsite muuttuu, kun voitetulla rahalla ei saa rauhaa, vettä tai pensaspaloilta turvattua omaisuutta. Ihmisen suhde muihin lajeihin, niiden riistämisen järjestelmät ja havahtuminen luonnon tasapainon ehkä peruuttamattomaan järkkymiseen on pakottanut huomaamaan hiljaisen perustan, jolle järjestelmämme on rakennettu. Yhä vahvempi usko tieteen auktoriteettiin pakottaa kuuntelemaan myös sitä tietoa, joka puhuu toislajisten eläinten kielestä, kulttuurista ja kyvystä kärsimykseen. Kuilu teorian ja käytännön välillä kasvaa, kunnes se tulee näkyväksi jo valtavirrassa.

Äkkiä kohti katsovat miljoonat silmäparit.

Taiteellisia reaktioita

Eläimen poissaolo on leimannut myös taidetta. Ensin eläin katosi maisemaan, sitten jopa maisemasta. Modernin taiteen kääntyessä 1900-luvulla kohti itseään eläimellä ei enää ollut minkäänlaista asemaa taiteen näkymissä. Jos kuva ei pystynyt enää puhumaan jaetusta, objektiivisesta todellisuudesta, kuinka se voisi tietää mitään eläimestä, luonnosta, toisista sisäisyyksistä? Eläimen poliittinen merkitys on noussut takaisin taiteen keskusteluihin vasta viime vuosina, sekä luonnon että riistokapitalismin samanaikaisesti ja samoista syistä kriisiytyessä. Ihmisen ja muiden lajien välille levittäytyvä kuilu esittää kysymyksensä myös sille, miten me itse taiteellista prosessia hahmotamme. Onko taiteellinen luominen vain ihmisen ominaisuus? Onko taiteen tehtävä puhua vain ihmisestä ja vain toisille ihmisille? Pysyykö taide ennallaan, jos suhteemme luontoon, yhteisöön ja toisiin lajeihin määrittyy uudella tavalla? Ihmiskeskeisyyden jälkeiseen aikaan siirtymistä valmistellaan sekä taiteen ja humanismin alueilla eläimyyden, ei- inhimillisen ja luonnon käsitteiden uudelleenarviointien kautta, taiteen ja aktivismin välisten rintamalinjojen samaan aikaan sekoittuessa. Eläin ei enää ole ekotaiteen kuriositeetti, vaan pikemminkin poliittisen ytimessä oleva avoin haava, joka vaatii myös luovan huomiomme.

Taiteelle keskeinen representaation käsite on leimannut toislajisten eläinten ja luontosuhteen käsittelyä nykytaiteessa. Kuvallisten esitysten paikkana taide on voinut pohtia tapoja, joilla käsityksemme eläimestä muodostuu, ja ravistella erilaisia tietämisen mekanismeja. Itse olen taiteellisessa työssäni tarkastellut näitä mekanismeja suhteessa tieteelliseen tietoon ja tieteen representaatioihin. Suomalaisista mediataiteilijoista mainittakoon mm. Perttu Saksa, jonka uusissa projekteissa ihmisyys peilautuu muiden kädellisten vieraudesta, tai Eija-Liisa Ahtila ja ihmisen mittakaavaansa pakottava kuusen muotokuva. Myös Salla Tykän tuotantoa voi tarkastella eläimyyteen liittyvän kontrollin, estetisoinnin ja toiseuden symboliikan teemojen toistumisen kautta. Näissä teoksissa kysymys eläimestä haastaa ajattelemaan ensi sijassa ihmisyyttä ja sitä, miten sen suhteessa tähän toiseen määritämme. Yritys tavoittaa tuo toiseus, kuten Ahtilan kuusiteoksessa, näyttäytyy aina yrityksenä: kuvalliset välineemme ja koko kuvan tekemisen perinteemme kantaa raskasta ihmisyyden painolastia, jota on kuvan keinoin vaikea kiertää. Yritys ei tässä tarkoita epäonnistumista vaan elettä, jossa juuri jotakin olennaista ihmisyytemme rajallisuudesta paljastuu.

Representaation käsitteeseen sisältyy kuitenkin myös edustuksellisuuden merkitys, joka ei ole niinkään epistemologinen kuin poliittinen. Yhtä tärkeää kuin pohtia eläimen esittämisen tapoja on pohtia sitä, millä tavalla se on edustettuna poliittisessa järjestelmässämme. Käsityksemme toisista lajeista syntyvät yhtä lailla tiedollisen, kuvallisen ja kirjallisen representoinnin puitteissa kuin valtaan liittyvissä konkreettisissa päätöksenteon mekanismeissa. Jos naiseksi ei synnytä vaan tullaan, niin myös eläin ja sen toiseus on rakennettua. Laki ja valtio muodostavat matriisin, jonka puitteissa ihmisen ja toisten lajien välinen kohtaaminen tapahtuu. Tämä matriisi ei ole teoreettinen vaan lihallinen, ja lihallistuu käytännöissä. Jos toteamme, että meidän on uudistettava suhteemme tosiin lajeihin johtaa se väistämättä myös poliittisen järjestelmämme ja yhteisöllisen ajattelumme syvälliseen uudistamiseen. Tämä tarkoittaa, että vain kuvallisten esitysten kriittinen tarkastelu taiteessa ei riitä: on myös luotava tapoja tarttua rakenteisiin, joissa eläimen toiseus konkretisoituu. Kuten kaikkien akuuttien eettisten kysymysten edessä myös tässä taiteen ymmärtäminen todellisuuttaa peilaavaksi, representoivaksi ei pelkästään riitä: on otettava vastaan haaste ja muutettava, häirittävä itse todellisuutta. Siksi eläinkysymys haastaa myös taiteen ja aktivismin rajoja.

***

Kysymys eläimestä on yhtä vähän marginaalinen kuin marginaalissa olevien ihmisten eettinen kohtelu. He eivät puhu, mutta esittävät meille haasteen pelkällä läsnäolollaan: heidän puhumattomuutensa ei oikeuta heitä kohdeltava toisin kuin puhuvia. Niin kuin kommunkoimaan kykenemättömien ihmistenkin suhteessa meidän on uskallettava kuunnella ja katsoa itseämme heidän kauttaan. Taide on mahdollisuus luoda tiloja, joissa itsestäänselvyyksinä tuntemamme ajattelun rakenteet kyseenalaistuvat. Ihmisen ja ei-ihmisen välillä olevaan olemukselliseen eroon perustuva yhteiskunta pitää sisällään ansan, joka on myös ihmiselle vaarallinen. Tämän eronteon perusteiden kriittisen tarkastelun tulisi olla yksi nykytaiteen keskeisistä poliittisista kysymyksistä.

Toisten Puolue – utopia yhteisöstä

Taiteilijana koolle kutsumani Toisten Puolue on 2011 alkanut poliittinen taide- ja aktivismiprojekti,

joka tarkastelee ulossuljettujen asemasta käytävä poliittista diskurssia yleisesti ja toislajisten

eläinten asemaa yhteiskunnassamme erityisesti.

Institutionaalinen politiikka tapahtuu juuri kielen tilassa, poliittisen keskustelun, äänen ja äänestämisen kautta. Kysymys eläimestä on radikaali, koska se haastaa kielen merkitystä yhteisöä rajaavana elementtinä. Voiko niillä, joilla ei ole pääsyä kieleen olla osallisuutta kieleen perustuvassa oikeus- ja poliittisessa järjestelmässä? Mitä tehdä kieliyhteisön ulkopuolisille – niille, jotka eivät voi itse vaatia oikeuksiaan? Olisiko mahdollista luoda poliittinen järjestelmä, jossa myös muunlaiset kommunkaation tavat kuin propositionaalinen kieli tulisivat otetuksi huomioon? Minkälaista on puhe, joka yrittää silloittaa railoa äänettömien ja puhuvien välillä?

Toisten Puolue – projektia varten haastattelin 12 ympäristöpolitiikan, oikeustieteen, eläinsuojelun, filosofian ja taiteen alan toimijaa. Esitin haasteteltaville ajatuksen siitä, että yhteisömme on lajien yhteisö, jonka määräenemmistöllä ei ole minkäänlaista edustusta yhteisessä päätöksenteossa. Kysyin, minkälaisia muutoksia nykyisessä yhteiskuntarakenteessa tulisi tapahtua, jotta näiden äänettömien kuuleminen tulisi mahdolliseksi. Minkälainen olisi yhteiskunta, jossa muiden lajien intressit olisivat tasavertaisesti huomioitu, ja minkälainen sen poliittinen järjestelmä? Minkälainen olisi tämän utopian perustalta hahmoteltu poliittinen puolue?

Haastattelujen kuluessa kävi selväksi, että kysymys suuntautuu kahtaalle. Toisaalta eläin- ja luonnonoikeuksiin perustuvan yhteiskunnan toteutuminen edellyttäisi yhteiskuntamme kaikki tasot läpäisevää kulttuurista murrosta. Toisaalta jo nykyisen yhteiskuntarakenteen sisällä olisi mahdollista toteuttaa huomattavasti vahvemmin eläinten ja luonnon oikeuksia huomioivaa politiikkaa. Keskusteluissa limittyivät utooppinen, radikaalisti nykyisiä käytänteitä kyseenalaistava pohdiskelu ja käytännönläheinen, konkreettisia toimenpiteitä painottava aktivismi. Haastattelujen pohjalta valmistin silloiseen Galleria Kalhama & Piippo Contemporaryyn video- ja ääni-installaation, ja koostin ehdotuksen eläinten ja luonnon oikeuksia ajavan Toisten Puolueen periaateohjelmaksi. Periaateohjelma julkistettiin näyttelyn auetessa sekä galleriassa että projektille avaamallani verkkosivulla. Samaan aikaan käynnistyi kannatuskampanja, jonka tavoitteena oli kerätä kannattajakortteja Toisten Puolueen merkitsemiseksi puoluerekisteriin. Toisten Puolue sai satoja kannattajakortteja ja yhteydenottoja.

Toisten Puolue on rekisteröity yhdistys, joka suunnittelee tulevaa toimintaa vuodelle 2013-2014 Suomeen ja ruotsiin. Projektia leimaa avoimuus ja utooppisuus ja pyrkimys tehdä näkyväksi poliittisen keskustelun spesismiä ja ihmiskeskeisyyttä. Vuoden 2011 periaateohjelma on ladattavissa osoitteesta www.toistenpuolue.fi